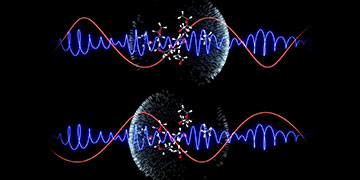

Researchers have used attosecond pulses (blue) and infrared pulses (red) to manipulate and even reverse the direction of electrons emitted from chiral molecules during ionization. [Image: Alexander Blech / FU Berlin]

Scientists in Europe and the United States have shown how to measure and manipulate the handedness of electrons emitted from chiral molecules thanks to a new source of circularly polarized attosecond laser pulses (Nature, doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09455-4). They reckon that their work could find applications in medicine and electronics.

Investigating chirality

Chirality is a well-known property of certain molecules, whose otherwise identical structure comes in “left-“ and “right-“ handed forms. But beyond this basic structural difference, researchers have also started to investigate the chirality of electron dynamics. Doing so effectively, however, calls for a source of circularly polarized photons arranged in pulses just attoseconds (10-18s) long—the natural timescale of electron dynamics.

Although attosecond laser pulses have to date been used to probe matter at both macroscopic and microscopic scales, imparting circular polarization to such pulses is no mean feat. The pulses are usually produced via high-harmonic generation from noble gases exposed to intense femtosecond radiation. But the collisions involved in this process prevent circular polarization from being transferred from the femtosecond to attosecond pulses, while imparting polarization afterward by directing the pulses to metal surfaces limits their wavelength and bandwidth.

Two years ago, Hans Jakob Wörner and colleagues at ETH Zürich in Switzerland showed how to overcome these problems using what they described as “a plug-in apparatus of unprecedented simplicity.” Their device splits a driving beam into two sub-beams with opposite helicities by directing the beam at a custom-designed half-wave plate (composed of two half disks) and then at a conventional quarter-wave plate. Focusing the sub-beams onto a gas target produces a coherent superposition with a linear polarization that rotates across the focal spot. This creates a similarly structured extreme ultraviolet beam, which upon propagation turns into two circularly polarized beams with opposite helicities.

Logging only those electrons that they detected simultaneously with the parent ion, they ended up with an asymmetric distribution characteristic of chiral molecules.

Electron behavior revealed

In the latest work, Wörner, Meng Han and other ETH Zürich coworkers, together with researchers in the United States and Germany, have shown how to exploit this device to probe the behavior of electrons within chiral molecules. They directed the circularly polarized attosecond pulse train at a target containing molecules of propylene oxide (C3H6O) and used a spectrometer to measure the energy and angular distribution of both the electrons and the associated cations given off in the process of ionization.

The researchers used this setup to observe what is known as photoelectron circular dichroism. Logging only those electrons that they detected simultaneously with the parent ion, they ended up with an asymmetric distribution characteristic of chiral molecules—recording unequal numbers of electrons in the incoming beam’s forward and backward directions. They also found that these asymmetries peaked for certain values of the electron energy (those expected for this specific molecule).

They then went on to overlap the attosecond beam in time and space with a linearly or circularly polarized near-infrared laser pulse. The combined beams also yielded an asymmetric pattern of photoelectrons but led to sidebands between the peaks in the energy spectrum (thanks, they say, to the creation of extra partial waves during the process of two-photon ionization). What’s more, the scientists found that they could vary the degree of asymmetry (dichroism) by introducing different attosecond delays between the two input beams, such that for one particular sideband they were able to switch the direction of electron emission, reversing the chiral signature of ionization.

Wörner and colleagues argue that their “attosecond chiroptical spectroscopy” could in future be used to determine the chirality of certain medical molecules with high sensitivity as well as help to improve spintronics and information processing. They also suggest it might reveal the missing link between a chemical compound’s chirality and its ability to act as a filter for electron spins. Given the possible role of coupled electronic-nuclear dynamics in this phenomenon, they say that the new spectroscopy “may offer a solution to this intriguing puzzle through its ability of temporally separating electronic from structural dynamics.”