[KrulUA / Getty Images]

[KrulUA / Getty Images]

We call it the second quantum revolution. Quantum technologies promise to transform our lives, from ultra-secure communications and supersensitive sensors to powerful computers capable of tackling problems far beyond the reach of classical machines. Yet today’s quantum devices remain limited in size and capability: Quantum communication links are limited in distance, and current quantum processors can handle only a modest number of qubits. Scaling up these systems is therefore a central challenge of quantum information technology. Optical quantum networking, powered by entanglement as a fundamental resource, offers a path forward.

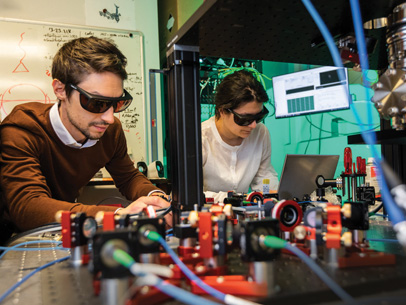

Quantum engineers developing a qubit-photon interface. [Couloir 3 / S. Borda]

Quantum engineers developing a qubit-photon interface. [Couloir 3 / S. Borda]

Scaling early quantum networks

Quantum communication was initially defined as the art of transferring quantum information between distant locations. This definition points to the central challenge that has driven the field for the past few decades: how to overcome the inherent losses when photons—the natural carriers of quantum information over a distance—propagate through optical media such as fibers or free-space links. Underpinning this challenge is the objective of scaling the size of quantum communication networks, both in range and in number of users.

The most mature approaches today rely either on switching techniques, which increase the number of users but do not extend the range, or on so-called trusted nodes, which can address both. Their impact can be appreciated in the context of ultra-secure communication enabled by quantum key distribution (QKD), arguably the most familiar and prominent application of such network architectures. In these systems, quantum operations occur across point-to-point links between network nodes. Intermediate nodes inevitably gain access to critical information once it becomes available in the classical domain, making them vulnerable to adversarial acts and requiring trust in the underlying systems.

Scaling quantum networks requires architectures that leverage the workhorse of the second quantum revolution: entanglement.

Trusted-node architectures have nevertheless driven quantum communication technology forward, leading to the deployment of impressive large-scale infrastructures across the globe that span both terrestrial and satellite optical links and incorporate industrial, high-performance quantum cryptographic systems. Further challenges relate to efficient integration: at the system level, for the development of cost-effective technology; at the network level, to enable coexistence with standard optical communication practices; and, crucially, at the application level, to lay the foundations of resilient, quantum-safe infrastructures based on a defense-in-depth approach combining quantum and classical cryptographic techniques for secure communication and beyond.

Quantum connectivity and the power of entanglement

Notwithstanding these advances, scaling quantum networks for general-purpose applications and without operational constraints requires architectures that leverage the workhorse of the second quantum revolution: entanglement. Entanglement—the non-classical correlations that can exist between particles—is a uniquely powerful resource, creating links with no analogue in the classical world. By envisioning quantum networking as the art of generating, distributing and allocating entanglement, it becomes clear that it is a key element not only for long-distance networks but also for scaling up quantum devices, which remain limited in size and capability. A notable example is quantum processors, which today can handle only a limited number of qubits.

In such architectures, entanglement is a resource to be consumed, underpinning a broad range of quantum-enhanced applications. It extends the scope of quantum cryptography to settings with minimal trust assumptions, compatible with the most demanding confidentiality requirements. It crucially enables quantum teleportation, allowing the transfer of qubits—the carriers of quantum information—across a distance without moving the physical carrier itself. Entanglement allows distant processors to collaborate in distributed quantum computing and enables quantum sensors to achieve sensitivities beyond classical limits, additionally guaranteeing privacy-preserving properties when required.

Realizing these capabilities would mark the advent of an era of quantum connectivity, comparable to the connectivity that defines our digital world today. In this perspective, scaling quantum information systems can be pursued along complementary directions. The first is extending entanglement across long-distance and complex quantum networks, pushing the range of secure communications and of distributed applications, including those involving sensors. The second is scaling up quantum computing by locally interconnecting quantum processor units (QPUs), so that networking becomes the means to overcome the limited qubit counts of individual devices. Both directions highlight the central role of optical quantum networking as the path forward to overcome current limitations in size, range and capability. Yet, with entanglement at the core of these architectures, demanding technological challenges must be addressed to realize its full potential.

A quantum internet for global-scale entanglement

The distance over which photons can propagate is fundamentally limited by transmission losses. In addition, the no-cloning theorem rules out any form of amplification of the quantum signal, as is routinely done in classical communication channels. In this context, a central challenge is how to distribute entanglement over long distances.

A first solution, which has seen remarkable progress over the past decade, is the use of satellites equipped with quantum technology to connect remote points on Earth. The Chinese Micius satellite offered pioneering demonstrations, distributing entangled photons to ground stations more than 1000 km apart and enabling satellite-based QKD. Several additional missions are now planned worldwide, with nanosatellite launches already actively underway.

A second solution, is the concept of the quantum repeater, introduced more than 25 years ago. The principle is to divide a long link into a series of shorter segments over which entanglement can be faithfully distributed. So-called entanglement-swapping operations are then used to connect adjacent segments via Bell-state measurements (i.e., photon detections), thereby extending entanglement across the entire distance. Central to this architecture is the use of optical quantum memories: coherent light–matter interfaces that can store photons and release them on demand with high efficiency and minimal noise. Their role is to synchronize the inherently probabilistic generation of entanglement across multiple links, thereby overcoming the exponential increase of communication time with distance in terrestrial fiber networks.

First demonstrations of quantum-repeater segments have already been reported, from pioneering laboratory works two decades ago to recent experiments in which telecom fibers are used over metropolitan-scale networks. Yet surpassing the direct-transmission limit remains a tremendous challenge today.

The quantum repeater provides the archetype for entanglement distribution over a linear chain of segments. More complex network structures with diverse topologies and multiple users could ultimately give rise to a future quantum internet, as envisioned by the late H.J. Kimble in 2008. Large research programs, such as the Quantum Internet Alliance in Europe or the National Quantum Initiative in the United States, are now pursuing the development of such architectures—not only at the hardware level but also, importantly, at the software level, tackling multitasking of quantum applications and adopting an application-driven approach for utility-scale deployment of next-generation quantum network infrastructures. Such efforts will guide the definition of pertinent and quantifiable performance metrics for such infrastructures, facilitating their wide-scale adoption.

A future quantum internet will rely on the distribution of entanglement via fiber-based repeaters and satellite links. [Illustration by Ella Maru Studio]

A future quantum internet will rely on the distribution of entanglement via fiber-based repeaters and satellite links. [Illustration by Ella Maru Studio]

Networking processors for scalable quantum computing

While global networks aim to extend entanglement distribution across long distances, a pressing challenge is the scaling of quantum computing itself. Solving real-world problems and addressing relevant industrial use cases will require a large number of error-corrected qubits. Current quantum processor units—across all qubit modalities, though for differing reasons—remain restricted to operating on only a modest number of qubits, which so far limits the reach of a quantum advantage.

A way forward for QPU scale-up via optical networking is to interconnect multiple processors locally.

A way forward is to interconnect multiple processors locally, in analogy with the modular architectures and horizontal scaling that have long driven the progress of classical computing and data centers. Once again, entanglement provides the essential resource for such interconnections, enabling processors to operate as a unified quantum system. In the mid-term, the drive to increase the number of qubits will also naturally involve linking larger numbers of modules.

Optical quantum networks are the backbone of future data centers, where modular quantum processor units (QPUs) built from different types of qubits work together and use shared entanglement to run distributed quantum algorithms. [Illustration by Ella Maru Studio]

Optical quantum networks are the backbone of future data centers, where modular quantum processor units (QPUs) built from different types of qubits work together and use shared entanglement to run distributed quantum algorithms. [Illustration by Ella Maru Studio]

A researcher develops a compiling technique to distribute a quantum algorithm between entangled quantum processor units. [A. Anice / Agence Oblique]

A researcher develops a compiling technique to distribute a quantum algorithm between entangled quantum processor units. [A. Anice / Agence Oblique]

Within each QPU, qubits can be distinguished between data qubits, dedicated to processing, and communication qubits, used to establish and share entangled states. In such an architecture, quantum circuits can be local, acting on qubits within the same QPU, or non-local, acting on qubits assigned to different QPUs connected through entanglement. Non-local operations can be implemented through primitives such as telegate (the remote execution of a quantum gate) and teledata, which transfers a quantum state between processors. These primitives are the building blocks of distributed quantum computing (DQC), enabling the partitioning of a given monolithic circuit corresponding to a specific algorithm into a set of circuits executed across multiple QPUs. In this way, distributed quantum algorithms can scale beyond the capacity of individual processors.

If one considers entanglement as a resource to be allocated and consumed (as in long-distance networks), then a requirement in this context is the development of efficient and robust software tools, called quantum compilers, that can map monolithic algorithms to distributed architectures while minimizing the required inter-device entanglement links. Strategies to simplify the quantum circuits and facilitate their execution by rewriting them into equivalent circuits optimizing the consumption of resources need to be compatible with diverse quantum architectures. Crucially, they need to incorporate the capacity to perform error-correction operations such that the distributed computing architecture is also fault tolerant, a requirement for achieving a computational quantum advantage in practice.

Central to this distributed vision is also the capability of QPUs to communicate by emitting or receiving photons through the network. Photonic interconnects are hence essential, as they provide low-loss, high-fidelity links between modules. The ability to interface with optical networks additionally opens the door to heterogeneous DQC, which can leverage the complementary strengths of different QPU architectures by interconnecting processors based on distinct qubit modalities. This approach offers a path toward versatile and effective quantum data centers that can readily be integrated into high-performance computing infrastructures.

Qubit–photon interfaces for quantum connectivity

Quantum networking requires the development of specialized hardware. As noted earlier, QPUs must first be able to communicate optically, requiring efficient qubit–photon interfaces, that is, quantum input/output ports, to couple to fiber networks. In photonic platforms, the photon itself encodes the qubit and can naturally be used for networking. For other qubit modalities, these interfaces take different forms.

For superconducting qubits, they rely on quantum transducers capable of converting microwave photons into the optical domain. Such devices are under active development using a range of approaches. On-chip implementations explored so far include electro-optic, electro-opto-mechanical, and rare-earth-ion-based transducers. Decisive metrics include the efficiency of conversion and the added noise. For other modalities that can directly emit optical photons, such as neutral atoms, ions or some solid-state qubits, optical cavities are required to enhance light–matter coupling and enable large collection efficiency. To meet the constraint of integration into QPUs, nanoscale cavity solutions are being developed, including optical waveguides such as nanofibers. In many cases, optical frequency conversion is also required to shift the collected photons to telecom wavelengths, thereby enabling compatibility with existing fiber networks and classical optical technologies.

With suitable photon interfaces available, QPUs can now be networked—that is, entangled. This entanglement can be generated either through the interference of emitted photons or through the absorption of entangled photon pairs. In a distributed architecture, many entanglement links will be required at different stages of circuit execution. These links will be consumed and, when needed, regenerated. Such networking will therefore rely on reconfigurable optical connections that can be dynamically orchestrated. Instead of being sparsely connected by limited point-to-point links, QPUs will form richly connected networks.

Architectural efforts that combine classical data center expertise in topologies and management control, advanced quantum-compiling strategies and distributed error correction are ongoing. We can foresee that these efforts will lead to advances specifically tailored to modular quantum computing.

Quantum memories: an essential building block

Fundamental to the quantum networking architectures described earlier are large photonic interconnects with storage capability. Optical quantum memories provide this functionality and, depending on the architecture, play various roles. As in quantum-repeater protocols, they can serve as entanglement-generation boosters by storing and synchronizing photons within the network and enabling asynchronous Bell-state measurements. More generally, they can store entanglement and deliver it on demand, thus increasing the interconnect speed. In heterogeneous architectures where photon wavepackets may differ significantly, quantum memories additionally offer the capability of efficient pulse shaping, enhancing the indistinguishability of the photons that must be interfered.

Building quantum memories is a major challenge. They rely on the reversible and coherent mapping of quantum states of light onto quantum states of matter. A successful approach for write/read devices makes use of large atomic ensembles, where photonic states are mapped into collective excitations of many atoms.

Highly efficient on-demand optical quantum memories can be created by using large ensembles of laser-cooled atoms. [LKB Paris]

Highly efficient on-demand optical quantum memories can be created by using large ensembles of laser-cooled atoms. [LKB Paris]

This line of research began more than 25 years ago, driven by seminal works on stopped light and on the Duan-Lukin-Cirac-Zoller protocol. It has since advanced with neutral atoms as well as rare-earth-ion-doped crystals. Related progress has also emerged from other solid-state platforms, such as color centers in diamond operated at cryogenic temperatures.

For networking purposes, the storage-and-retrieval efficiency is a critical metric. As an example, an increase in this efficiency from 60% to 90% drastically reduces, typically by two orders of magnitude, the average time for entanglement distribution over a distance of 500 kilometers, with only a few entanglement-swapping steps. Recent years have seen significant progress in this direction. Laser-cooled alkali-atom ensembles have been used to push the efficiency above 90% and now form the technological basis of industry-grade quantum memories. Along with other platforms, each with distinctive features, they contribute to a nascent commercial offer in the field. The next generations of quantum memories will further advance key performance metrics, including storage time, bandwidth and multimodal capacity, continuing to expand the capabilities of quantum networking architectures.

Synergies for quantum connectivity

Bringing together all the elements of quantum networking—both for long-distance networks and for quantum data centers—is a multifaceted endeavor that will require important scientific and technological breakthroughs, as well as strong synergistic efforts across a wide range of disciplines.

Welinq, which the authors cofounded, in 2025 released QDrive, an industry-grade racked quantum memory with a 90% storage-and-retrieval efficiency and >99% fidelity. [A. Anice / Agence Oblique]

Welinq, which the authors cofounded, in 2025 released QDrive, an industry-grade racked quantum memory with a 90% storage-and-retrieval efficiency and >99% fidelity. [A. Anice / Agence Oblique]

While integration is not a major concern for first adopters, it will become of utmost importance in the longer term for scaling up quantum devices and practical applications. Minimizing the size, weight and power (SWaP) footprint will require significant progress in on-chip quantum photonics. Integrated circuits combining photon sources, single-photon detectors and routing elements will enable compact, high-performance networks for both long-distance communication and modular computation. Low-SWaP lasers and modulators will further simplify qubit addressing and control. However, high-density photonic integration introduces challenges related in particular to cross-talk, so designing optimal circuits is a delicate and demanding task.

High-profile programs such as the Chips Acts in Europe and the United States, although targeting primarily the semiconductor industry and supply chain, will also benefit photonics. A pilot-line development approved recently in Europe, which in fact covers all major qubit modalities, underscores the role of such integration efforts in preparing the ground for the wide-scale adoption and deployment of these technologies.

Among the components to streamline, efficient photon sources that can match the needs of quantum-network architectures are also a key requirement. High-purity, indistinguishable single photons or entangled photon pairs are critical, as their characteristics directly impact the entanglement-distribution rates. Spontaneous parametric down-conversion sources remain the workhorse. They can support heterogeneous connectivity through highly frequency-non-degenerate photon pairs, for instance linking matter systems to telecom networks, and their bandwidth can be engineered to match interface requirements. Multiplexing strategies can further increase the effective rate of inter-device entanglement generation. Looking ahead, deterministic single-photon emitters based on quantum dots or neutral atoms coupled to cavities are expected to open new capabilities. Yet the source characteristics must be carefully tailored to those of the qubit devices to ensure compatibility.

Pushing the boundaries of scalable quantum networks requires bringing together quantum optics and classical networking.

Pushing the boundaries of the technology backbone of robust and scalable quantum networks requires an interdisciplinary approach, bringing together quantum optics and classical networking. Likewise, at the software and application level, a significant interplay is required between quantum algorithms and cryptography and their classical counterparts, also informed by end-user needs. From certified ultra-secure communication to blind, secure and verifiable quantum computations, and from distributed quantum sensing to error-corrected logical operations within data centers, the full spectrum of functionalities and services enabled by quantum networking is, in fact, yet to be explored.

A rapidly expanding quantum-networking industrial ecosystem across this spectrum—for instance, Welinq, which we cofounded; NuQuantum in Europe; and Qunnect, Cisco and IonQ in the United States—bears witness to its major impact potential.

Scaling is the defining challenge of the second quantum revolution. By harnessing entanglement, optical networking will enable quantum technologies to expand in scope and scale, anchoring the next generation of quantum information infrastructures. The era of quantum connectivity is about to begin.

Eleni Diamanti is at LIP6, CNRS, and Julien Laurat is at Laboratoire Kastler Brossel, both at Sorbonne Université, Paris, France. Both authors are cofounders and scientific advisors of the Paris-based quantum networking startup Welinq.

For references and resources, visit: optica-opn.org/link/scaling-quantum.