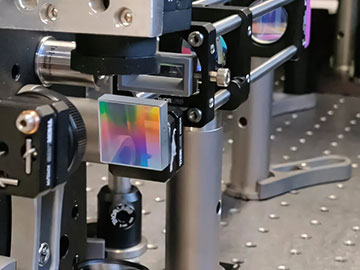

Scientists have exploited dispersion from a diffraction grating to improve the d-scan technique, which is used to study femtosecond pulses by recording the signal of a nonlinear process over a range of dispersions. [Image: Lund University]

Lasers generating pulses lasting just a few femtoseconds (10-15s) are used by scientists to study exceptionally fleeting processes such as energy transfer in photosynthesis. Surgeons, meanwhile, exploit them to carry out delicate operations on the eye, and manufacturers use the light to carve out tiny structures. Nevertheless, characterizing such brief flashes has proved a headache—electronics are too slow for the job and optical alternatives often prove complicated to carry out.

Now, researchers in Europe have shown how these shortcomings might be overcome by exploiting a previously unused property of diffraction gratings to improve a technique known as single-shot dispersion-scanning (Optica, doi: 10.1364/OPTICA.572768). They have used the new approach to analyze a range of pulse lengths, including those lasting more than 100 femtoseconds (fs). These relatively long pulses are particularly relevant to industry and medicine but, counterintuitively, are also the hardest to pin down. This suggests that the new work could benefit, among other things, precision micromachining, real-time process monitoring and medical device fabrication.

A dispersion fingerprint

Dispersion-scanning involves manipulating a laser pulse’s spectral phase via positive and negative group velocity dispersion while recording the signal of a certain nonlinear process—usually second-harmonic generation—for a range of dispersions. The resulting spectogram provides a fingerprint that allows a pulse’s temporal and spectral properties to be worked out using numerical algorithms.

The technique was originally proposed and demonstrated in 2012 by researchers at Lund University in Sweden and the University of Porto in Portugal (with the latter then spinning off a company, Sphere Ultrafast Photonics). Since then, researchers have employed a variety of optical components to provide the necessary dispersion, including prisms, gratings and filters. They have also shown how to carry out the scan in a single shot by varying dispersion across the beam and then capturing the spatially resolved nonlinear spectrum using an imaging spectrometer, achieved using prisms, transverse second-harmonic generation crystals or multiple reflections within a glass plate.

However, all demonstrations to date have relied on material dispersion (wavelength-dependent refractive index). Because dispersion rises in proportion to the square of a pulse’s duration, very short pulses are relatively easy to characterize. For longer pulses, in contrast, the optical components used to scan the dispersion impose an upper limit of about 100 fs.

Because dispersion rises in proportion to the square of a pulse’s duration, very short pulses are relatively easy to characterize.

Leveraging diffraction gratings

In the latest work, Cord Arnold and colleagues in Sweden, Spain, Portugal and the United Kingdom have shown how diffraction gratings can be used to overcome this problem. As they point out, there has been much study of angular dispersion, the variation in path length caused by frequency-dependent diffraction angles. In particular, this phenomenon gives rise to a spatially dependent group delay dispersion in planes other than that of the grating. This variation in dispersion causes a distribution of pulse duration across the beam, and it can be much larger than that due to material dispersion.

Making use of this phenomenon involved overcoming a couple of hurdles. For one thing, the finite nature of laser beams leads to a separation of a pulse’s different frequencies in space, which is a problem given the need for a constant spectrum wherever the nonlinear signal is generated. What’s more, angular dispersion leads to negative, as well as positive, group delay dispersion. The researchers minimized these problems by placing the diffraction grating and nonlinear crystal as close as possible—imaging the diffraction plane onto the crystal.

Demonstrations and future directions

To demonstrate their scheme, the researchers characterized the pulses from a commercial infrared chirped-pulse amplification laser. They used a single diffraction grating to produce the spatially dependent group delay dispersion and a combination of a cylindrical and spherical lens to optimize the laser’s intensity reaching a 5 µm-thick nonlinear crystal. They then spatially resolved the spectrum of the second-harmonic signal generated by this crystal with an imaging spectrometer.

They carried out their measurements with two different sets of pulse durations: between 50 and 80 fs, and at 170 fs. In both cases, they say, they demonstrated single-shot temporal and spectral pulse characterization.

Arnold and colleagues maintain that, in addition to increasing the range of pulse lengths, their system is easier to operate than earlier setups, as it doesn’t require components to compensate dispersion at the outset. The setup also allows pulses with arbitrary chirp to be measured, which they can do simply by changing the imaging plane.

The team reckons that the new scheme could measure pulses as long as 300 fs, arguing that the main challenge in extending the technique’s reach will not be increasing dispersion itself but instead boosting the spectral resolution of the imaging spectrometer. The scientists add that the technique could be made more versatile by extending the simple plane wave model they used in the current work—requiring the use of large, spatially uniform beams—to investigate the effect of a curved wavefront.