NewSpace is opening up the door for new opportunities in optics and photonics. [Image: gorodenkoff/ Getty Image]

Optics and photonics has been used in spacecraft for decades, primarily for imaging the Earth and celestial objects. There is now excitement around the wider use of optics, particularly for optical communication, brought about by a more commercial and competitive space industry referred to as “NewSpace.” The moniker reflects the transition from a government-regulated space industry (“OldSpace”) to an industry dominated by private investors, companies and startups.

The Satellite Industry Association estimates that in 2024, the space industry brought revenues of US$293 billion, comprising US$108 billion in service revenues, US$155 billion from sales of ground equipment, US$9.3 billion for launch services, and US$20 billion for satellite manufacturing. Manufacturing revenue grew 17% over the previous year, and about 81% of it—roughly US$16 billion—was for commercial communications. Some of that revenue was spent on laser- and optics-based components and systems. Other applications included remote sensing and surveillance, navigation, science and R&D. US companies received 69% of the commercial satellite manufacturing revenues.

The commercialization of space

The Cold War pushed the early space industry to become a prestigious but expensive endeavor. Military applications, such as missiles, prioritized performance and reliability over cost-effectiveness. High-value payloads, such as the James Webb Space Telescope, require high reliability and long lifetimes in space, raising the cost. Human space flight continues to captivate the imagination but requires large, expensive rockets to carry the substantial payload required to sustain humans in space.

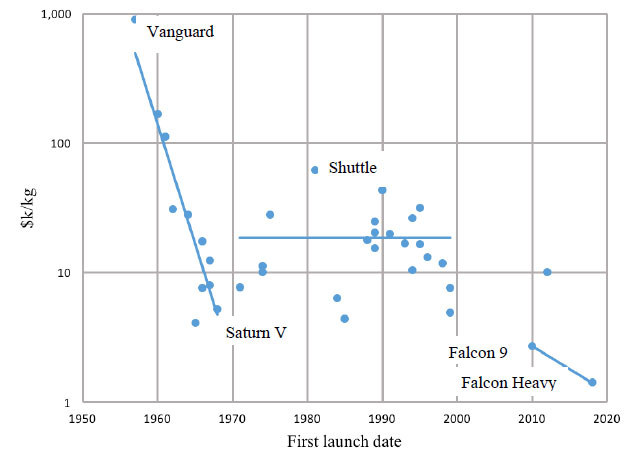

Launch cost per kilogram to LEO versus first launch date (adjusted for inflation to 2018). [Harry Jones, “The Recent Large Reduction in Space Launch Cost” (NASA Technical Reports Server, 2018)]

Many factors drive up the cost of space optics. The components need to withstand the high-vibration launch and harsh space environment. Some components require hardening against radiation, particularly for high orbits. The systems must remain in operation for many years without the opportunity to adjust or replace the parts. Contracts are awarded on a “cost plus” basis that reduces incentives to reduce cost. And the investment is spread over small volumes, often using hand assembly, which raises the price per unit.

For decades, government space agencies regulated and managed their domestic space industries. In the United States, this NASA-led OldSpace model is associated with low volumes, low tolerance for failure, complex designs, detailed oversight, and expensive qualifications for suppliers that take years to complete. Politics also sometimes took priority over decision-making, and the supply chain was geographically dispersed, in part to protect government funding. Consequently, this model was criticized for becoming too risk averse and expensive, which restricted innovation and market growth.

Policy changes led numerous private-sector launch companies to enter the market in the last 20 years, peaking in 2015 with the founding of over 50 companies in that year alone. Nearly all of these companies proposed to use low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites for applications in Earth observation or communications. LEO is particularly interesting for communications because the one-way physical latency to ground is only 2 to 4 ms, compared with satellites in geostationary orbits that have one-way delays greater than 100 ms.

SpaceX led the way to dramatically reduce launch and satellite costs with its startup company culture, lean workforce, flat management structure and vertical integration. The company controls all phases of the product lifecycle and uses a fixed price model that creates incentives to reduce cost. It has reduced launch costs by over 10× in a decade to less than US$2,000 per kg of payload, amounting to only tens of millions of dollars per launch. In comparison, NASA estimates that the cost of its space shuttle launches was nearly US$2 billion per launch (adjusted for inflation to 2025), amounting to about US$70,000 per kg.

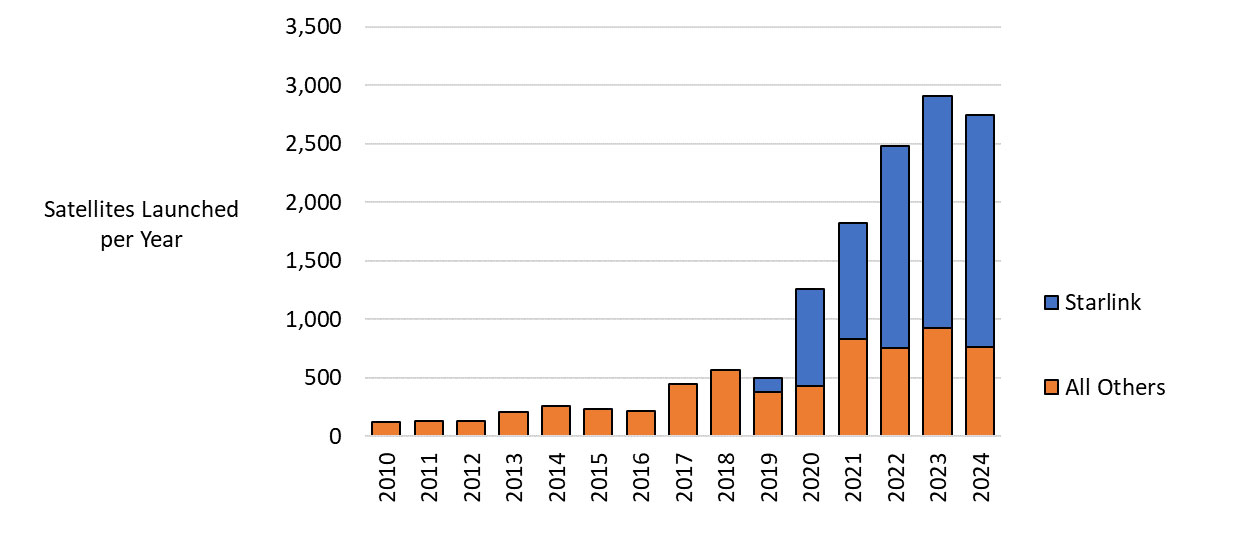

SpaceX’s growth surged in 2019, when it began deploying its constellation of Starlink satellites for wireless communications. Figure 2 shows the number of satellites launched per year, with about 8,000 Starlink satellites currently in orbit, and nearly all of them operational. The company has a license to operate 42,000 satellites by 2040, not including those that return to Earth within their relatively short five-year lifetime. To this end, it has reused some booster rockets over 20 times, with each rocket carrying as many as 20 or more satellites per launch.

SpaceX is also launching payloads and deploying satellites for the US Department of Defense, which has embraced the lower-cost launch model. As the market leader, SpaceX is in an enviable position: It has increased launch volume and gained market share. This gives SpaceX a market advantage that may be difficult for competitors to overcome, at least in the short term.

However, the expansion of SpaceX and its Starlink constellation have raised concerns about overconcentration of market power into one company and its CEO. Competition is growing from Europe and China to offer competitive launch capacity and satellite-based services, but the progress is slower; for example, China’s SSST only began deploying satellites for its Qianfan constellation in mid-2024. This new global competition is happening as the world is moving toward more protectionist trade policy, which may force customers to balance decisions between cost and performance versus the geopolitics of the moment.

There’s also the risk of a market cycle. According to an analysis by Quilty Space, if all the companies that have filed for satellites were approved and deployed, an improbable 478,000 satellites would be in space by the end of 2030. McKinsey & Company warned in an April 2023 report that a surge in launch capacity could result in an oversupply if competitors succeeded in their goals. McKinsey’s high estimate is around 65,000 deployed by then, requiring about two times the launch rate of today; its low estimate is 27,000.

McKinsey also warned there could be a shortfall in capacity if the industry fails to meet supply goals. Companies that don’t meet goals can lose their licenses to deploy more satellites or receive government support. Or satellite demand could slow if satellite lifetimes are longer than expected, or if the business strategies of Starlink and others fail to be profitable.

New satellites launched per year. [From J. McDowell at www.planet4589.org and www.newspace.im/newspace]

Optical satellite communications

Free-space optical communications is becoming a major technology of the NewSpace economy. The first demonstrations were over 30 years ago, and there have been many recent demonstrations and plans for its deployment. SpaceX has deployed laser-based optical communications in its Starlink constellations since 2020. Optical communication offers several advantages over RF communications: nearly 100× greater bandwidth; lower size, weight and power; greater security and less-regulated transmission.

The optical system onboard the spacecraft is called a Laser Communication Terminal (LCT) or Optical Communication Terminal (OCT). It can be housed with a CubeSat, which offers a standard form factor and interface. The spacecraft contains multiple lasers operating at as much as 100 Gbps per channel. The LCT operates between satellites; RF is still used to communicate to and from ground stations. The value of various optical subsystems and cubesats are in six figures: about US$100,000 to US$1 million each, but the prices will likely come down over time.

The relatively short five-year lifetime of Starlink satellites means that the lasers and optics are a “consumable” item, requiring replacement every few years and bringing recurring revenue to suppliers. In interviews for this article, estimates for the value of optical systems manufactured last year by and for NewSpace satellites range to as much as US$500 million to US$1 billion, and doubling in five years.

The future of NewSpace optics

The OldSpace industry was well-suited for disruption by a lower-cost business model, and launch cost has always been the primary constraint in the space business. The lower launch cost of NewSpace opens new opportunities for optics and photonics suppliers, particularly those that can innovate rapidly. It can lead to entirely new design decisions, such as the use of off-the-shelf technology that is lower cost, robust and well-tested. It can allow for redundancy or replacement that were prohibitive before.

Starlink’s designs and supply chain may already be in place, but suppliers can look for business with other satellite makers or new communications applications, such as complementing RF with laser communication between satellite and ground, quantum links for QKD, or links to high-orbit satellites or deep space. And optics is used to track stars for navigation, for docking and collision avoidance and for new applications in remote sensing and surveillance. There is even speculation about the use of optics for microgravity manufacturing and space debris removal, and the US military is planning for constellations of satellites for missile warning and tracking.

The OldSpace market is not going away and remains attractive for the companies that address it—production volume may be a fraction of that for NewSpace applications, but unit prices can be large multiples greater. Although there are no reliable estimates for the revenues to optics and photonics suppliers, the NewSpace and OldSpace segments may be approximately comparable, at least until recently. The total space optics market may be about US$1-2 billion this year and growing at a remarkable 10 to- 20% per year. Importantly, it is riding on a market that is headed toward US$1 trillion in a few years, if all goes as planned.

Tom Hausken (thausken@optica.org) is a senior science advisor at Optica.

References and Resources

Harry Jones, “The Recent Large Reduction in Space Launch Cost” (NASA Technical Reports Server, 2018).

Edwin Cartlidge, Lift-Off for Space Lasers (OPN, October 2024, p. 26-33).

Andreas Thoss, Laser Communication Terminals Spark a Silent Revolution (Photonics Spectra, March 2025)

Sandra Erwin, “Demand for satellites is rising but not skyrocketing” (Space News, 4 December 2023)

Chris Daehnick, John Gang, and Ilan Rozenkopf. McKinsey & Company, "Space launch: Are we heading for oversupply or a shortfall?" April 2023.