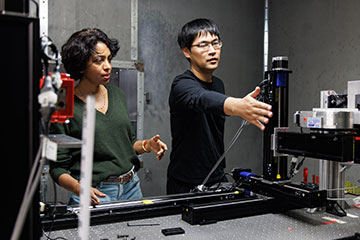

Mini Das (left) and Jingcheng Yuan at the University of Houston have shown how to combine X-ray attenuation, differential phase-contrast and dark field imaging in a single shot by appropriately positioning a mask (in front of a sample) with respect to the detector. [Image: University of Houston]

Scientists in the United States have devised a new X-ray imaging scheme that gathers information beyond that available with conventional attenuation-based techniques (Optica, doi: 10.1364/OPTICA.578430). The new technique takes information in a single shot without requiring lengthy exposures or expensive detectors. The researchers say that the greater detail captured using their methodology could improve both medical diagnoses and material analysis.

Greater contrast

Traditional X-ray imaging relies on the concept of attenuation, providing views of internal organs and the insides of various structures by recording the extent to which different tissues or materials absorb X-rays. This technique has played a fundamental role in medicine, engineering and other disciplines for decades but is often unable to distinguish between materials with similar attenuation coefficients.

More recently, researchers have developed two new approaches to generate extra contrast. One of these records how X-rays’ phase shifts as they travel through a medium thanks to differences in refractive indices at small scales. The other approach, known as dark-field imaging, instead exploits scattering over very small angles by micrometer-scale structures.

Putting these alternatives into practice, however, involves some major challenges. Numerous specific schemes have been devised, but they often call for very coherent X-ray sources, extremely high-resolution detectors and advanced gratings. Plus, in many cases these costly setups require components to be precisely aligned and radiation to be delivered in multiple blasts—yielding high overall doses that can pose health risks, particularly for children and small animals.

Improved single-mask method

In the latest work, Jingcheng Yuan and Mini Das at the University of Houston report improvements to what is known as the single-mask method. This involves using X-rays to illuminate a plane made from strips of alternating low- and high-absorption material that is positioned just in front of a sample, which is some distance from a detector. This way, the pattern of radiation cast by the mask onto the detector is shaped by the various attenuations, refractions and scatterings taking place in the sample.

Yuan and Das showed it is possible to carry out this method in three different ways without changing the apparatus. One option, already demonstrated by themselves and others, involves positioning the mask so that each peak in the projected pattern hits the detector at the boundary of every other pixel. This “differential phase-contrast” arrangement, in the absence of any sample, leaves no pattern on the detector.

The first of the two new alternatives that they propose involves arranging the mask to capture dark-field images. Rather than project radiation onto pixel boundaries, this setup instead directs X-ray beamlets at the center of every other pixel, creating a series of alternating bright and dark regions on the detector.

Yuan and Das showed it is possible to carry out this method in three different ways without changing the apparatus.

For their third arrangement, the researchers combined the other two options by positioning the mask so that the peaks in its projection fall on every third pixel boundary. The result is a pattern that repeats once every three pixels, each time yielding two equally illuminated pixels and one dark one—in other words, a superposition of the previous two patterns.

Testing and hurdles

The researchers tested their scheme experimentally using a tube containing a graphite rod, a number of plastic beads and diamond powders with varying grain sizes. They found, as expected, that the differential phase-contrast better distinguishes between the different objects in the sample than does standard attenuation imaging. They also showed that dark-field imaging, while only revealing some of the objects in the sample, readily picks out the powered materials from the rest.

Furthermore, the researchers demonstrated the virtues of bringing together the different imaging modalities by taking pictures of a dried fish. By combining attenuation and dark-field imaging, they were able to capture both the overall structure of the fish and microstructures within it.

Yuan and Das argue that their method—requiring only low-dose single shots and low-resolution detectors—would make medical imaging significantly faster, more efficient and practical than is possible with existing techniques. They also reckon it would be suited to a range of industrial applications, such as rock analysis for the petroleum industry and real-time monitoring of engineered components.

However, they point out that hurdles remain. They say that their system works well for X-ray spot sizes, a crucial determinant of beam coherence, of up to 50 micrometers. But they note that clinical radiography employs much larger spot sizes, usually about 1 millimeter, which would yield unacceptably blurry mask patterns on the detector plane if used in their system. One possible solution to this problem, they suggest, would be adding a mask at the X-ray source as well as at the sample.