[Image: Getty Images]

Three months ago, as 2020 dawned, the biggest issue on Europe’s plate seemed to be the upcoming year of potentially brutal trade negotiations after the United Kingdom’s Brexit withdrawal from the European Union. Signs had also appeared of slowing growth in some of the continent’s major industrial economies, especially that of Germany. And, from halfway around the world, news was in the air of a novel, highly infectious coronavirus in China that was proving difficult to contain—and that, some worried, could threaten global supply chains.

What a difference three months makes. In that time, the coronavirus-induced disease, COVID-19, has morphed into a worldwide pandemic. Efforts to slow its spread have caused much of economic activity, in Europe and elsewhere, to grind to a halt. The COVID-19 crisis has swept off of the table not only the U.K.’s exit from the EU, but virtually every other topic of daily news. And some have wondered if the EU itself, as a political and economic force, will weather the crisis.

The pandemic story has unfolded with breathtaking speed, and the photonics community, like others, is largely being pulled along by the tsunami. With the situation changing daily, it’s difficult to say anything especially useful about the long term. What follow are some snapshots of the impact the crisis is having on Europe and European photonics right now, both in the large arena of funding, travel and trade, and in the more intimate sphere of daily work and life.

Hard-hit continent

While the United States now reigns as the number-one single country in reported cases, on a regional basis it’s Europe that has occupied center stage in this baleful drama. As of the morning of 3 April, according to data from Johns Hopkins University, USA, total reported COVID-19 cases in the 27 states of the European Union, plus the United Kingdom, Switzerland and Norway, amounted to 514,841—more than half of the global total of 1,017,693.

Europe’s disproportionate share of reported COVID-19 deaths has been greater still. The 37,945 such deaths in Europe as of 2 April accounted for more than 71% of world deaths from the disease. As has been widely reported, Italy and Spain have been particularly hard hit, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the total reported COVID-19 mortality in Europe—though there are signs that both the case count and deaths may have plateaued in both countries.

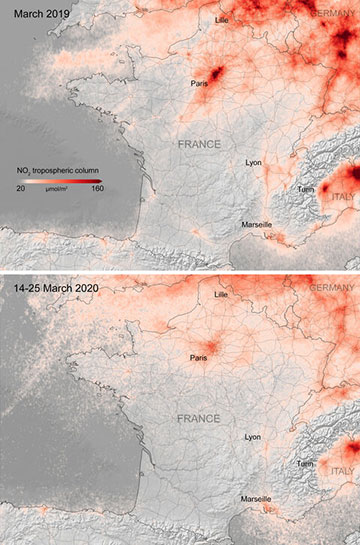

Mixed blessing. Satellite images from ESA's Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite show a dramatic reduction in nitrogen dioxide pollution over a range of European cities—attributable to the coronavirus-related drop in industrial and commercial activity. [Image: ESA]

Economic toll

Beyond the human costs, grim signs are emerging of the coronavirus’ toll on Europe’s economy at large. For the 19 EU member states in the euro currency zone, the IHS Markit manufacturing purchasing managers’ index—a popular barometer of economic health, based on surveys of private-sector senior executives—shrank to 44.5 in March 2020 from 49.2 in the previous month. That constituted the largest one-month decline in the index since April 2009, in the heyday of the late-2000s financial crisis. (Any reading below 50 in the index is considered a signal of deteriorating business activity relative to a month earlier.)

Satellite data have offered another window into the coronavirus’ economic impact. Images from the ESA’s Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite show a dramatic year-to-year decline in detected nitrogen-oxide concentrations over a range of major European cities—an outcome of the lockdown orders that have closed businesses and crimped economic activity across the continent.

The coronavirus production hit comes even as growth in Europe at large appeared already to be slowing. Germany, for instance, had already logged zero economic growth in the quarter ended December 2019—when COVID-19 seemed only a distant threat.

Mixed photonics picture

Wenko Süptitz, SPECTARIS, Germany.

What these new realities mean for photonics is not entirely clear, however, as the crisis has affected different countries and sectors to different degrees. For example, Wenko Süptitz, the head of the photonics division of the German industry organization SPECTARIS, pointed out in a 26 March interview with OPN that medical-technology firms are among those listed in Germany as essential operations for battling the coronavirus. He says that “quite a few” of the organization’s member firms in photonics, involved in making components for biosensors and other technologies, have applied to be listed as critical to such efforts.

On the other hand, as the crisis initially took root in China, Süptitz says that supply-chain disruptions for printed-circuit boards (PCBs), a necessity in many optoelectronic products, put the squeeze on a variety of firms in Germany as their stocks of PCBs from China ran dry. The fact that China seems to be recovering from the crisis could ameliorate that situation, according to Süptitz.

In general, Süptitz says that photonics companies seem to be “in the same flow of actions and situations as most of the other high-tech companies” in Germany with respect to the current crisis. Süptitz also points to actions of the German government to soften the economic blow and, potentially, allow companies to keep functioning without substantial staff reductions. One such program is the so-called Kurzarbeitergeld (“short-time worker money”), a set of government wage subsidies that allows companies to pay workers a portion of their regular wage and thereby to prevent layoffs.

The strategy, Süptitz notes, “worked quite well” during the 2008–09 financial crisis. COVID-19 could put the system to a new test, however; the Financial Times reports that, as of 12 March 2020, the number of companies that had applied for Kurzarbeit subsidies in the current crisis was nearly five times higher than the number that used them during the 2008–09 recession.

The SME dimension

More broadly, how well many photonics companies weather the crisis could depend on how well governments lend a hand to small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in particular.

Roberta Ramponi, CNR–IFN and Politecnico di Milano, Italy.

“Photonics is mainly based—for sure in Europe, but I think in practically all over the world—on SMEs,” says Roberta Ramponi of the Institute for Photonics and Nanotechnologies of National Research Council (CNR–IFN) and Politecnio di Milano, Italy. “And these, of course, are the most fragile in this kind of situation, because they may not have the critical mass and solidity to survive a long crisis.” Ramponi hopes that governments “will understand this aspect,” and provide the requisite support to carry SMEs through the storm.

OSA Fellow and 2018 OSA President Ian Walmsley, the Provost of Imperial College London, echoes those concerns with respect to the U.K. economy. The photonics industry, he notes, while one of the bigger sectors in the U.K., is “largely made up of small firms, and whether those firms can make it through the current crisis is an open question.”

On the other hand, interestingly, Walmsley notes that some firms in the startup domain, such as those in quantum technology, could push through. “If you’re in a phase where you’ve got some investment capital, and you weren’t expecting to generate revenue for two years, you can probably work through it,” he says.

Solution-providing role

Notwithstanding these uncertainties, both Walmsley and Ramponi stress that photonics will be one of the key technologies that will help guide the world through the current wilderness.

Ramponi notes the centrality of photonics in a variety of areas, such as diagnostics and biomedical research, that are core to the battle against COVID-19. The European photonics community, she says, is working to educate both government authorities and end-user communities on the need to support photonics research, and on “how much photonics can help now and could possibly also help in the future preventing this sort of situation.”

And photonics has pushed solutions well outside of the lab, Walmsley adds, at a time when many in the world have been forced to carry on their work and lives ensconced in home offices.

Ian Walmsley, Imperial College London, U.K.

The very fact “that we can now talk easily in such distant and remote locations—from our homes—is enabled by photonics,” he told OPN on a videoconference call. “We have to be thinking about what the opportunities [for photonics] look like in the future. They’re going to be there.”

Funding and doing science

Meanwhile, Ramponi, Walmsley and numerous others face the practical need to continue to manage scientific projects, funding and staff amid the current disruptions.

From an EU perspective, Ramponi notes that the scientific community is “in the transition period between the previous [EU funding] framework program, Horizon 2020, and the next one, Horizon Europe.” That is “quite a delicate period,” she says, “because you have to set up all of the programs and the budgets for the next seven years, and it’s not easy to do that in an emergency situation.”

Funding agencies, both in the EU and the U.K., have tried to make the job a bit less difficult by relaxing deadlines both for new funding applications and completion of existing projects (even as agencies in both areas have put new coronavirus-related work on a fast funding track). Yet even that largesse has created new administrative challenges, according to Ramponi.

“The big issue is with people under contract on those [existing] projects,” she says. The funder often “will give you the possibility of postponing the deadline, but you don't get more money to pay the people.” So, unless additional money can be found to meet that payroll, “you will still have the time, but no longer the people in some situations.”

Student limbo

When the word came through that nonessential labs would be closed at CNR and the universities, Ramponi says that “what we did was try to finish, in the fastest possible time, the experiments that we were running,” and to progressively close the labs at that point. The aim was to create a large amount of data that could be analyzed during the coronavirus-imposed shutdown of experimental work.

Rocío Borrego-Varillas, CNR-IFN, Italy.

Rocío Borrego-Varillas, a staff researcher at CNR–IFN, says that for her it was “not a big difference, because I had so much paperwork to do that I’m just using these days to finish paper writing or data analysis and so on.” But, she adds, “for the Ph.D. and master’s students, it can be a more serious issue” until they can resume experimental work.

Walmsley adds that at Imperial, with non-coronavirus-relevant labs effectively shut down, “Ph.D. students are needing to rethink what their degrees might look like, in light of experiments that may or may not be able to happen. PIs are thinking about what happens if project deadlines come up and they haven’t completed their research. So we are engaging with funders to understand what that means, and how we can work together to meet the project objectives.”

Indeed, OSA Fellow John Dudley of the Université de Franche-Comté, Besançon, France, stresses the importance of distinguishing the experience of senior researchers, who will feel relatively few long-term effects, and junior researchers and students, for whom the experience is apt to carry a profound impact.

“It’s the younger people who are just starting, who come in with hope, with new ideas, with ambition, with impatience,” says Dudley. “Most of us have been around for long enough to realize that there are always ups and downs, and you just ride them. But when you come in with hope and enthusiasm and energy, and then you're suddenly just stopped—it’s extremely hard.”

Tooling up for distance learning

In many ways, members of the European photonics community have faced the same problems that legions of others have faced, amid the need to hunker down and find ways to work from home until the crisis has passed.

One aspect that several of the contacts OPN spoke with suggested has gone relatively smoothly has been the transition to distance learning for lectures, coursework and other education. The web tools to support distance learning “are very well developed,” says Ramponi, adding that staff received a great deal of technical support in ramping up. It helped, she says, that the transition to distance learning at Politecnico di Milano occurred “just before the beginning of the semester, so there were a few days to organize things.”

At Imperial, Walmsley says that setting up for remote working, and remote education, in a very short period “took an immense amount of effort,” but he believes that it will pay long-term dividends. “We’ve learned very rapidly how to do online education by building online communities in a more effective way. That will impact how we do teaching in the future as well.”

John Dudley, Université de Franche-Comté, France.

In terms of how the teaching is conducted during the crisis, Dudley says that the emphasis at Franche-Comté has been not to make things even more stressful than they already are. “The clear message has been, ‘We realize that this is a difficult period for both staff and students, and we know it takes time to adapt. So don’t try to follow the same rhythm; don't try to demand as much.’”

The other side

Even as they deal with the current disruptions, Walmsley says that people still need to think about life on the other side. “The past two weeks has really been about, How do you make the immediate decisions that are needed to get you into a sort of lockdown steady state?” he says. “But in the next few weeks, we’ll have to start thinking about, What does the world look like next year? And what does the world look like the year after that?”

Some of that, according to Walmsley, will rest in the mundane details of restarting current operations. “It’s one thing to turn everything off, but when you go to turn it back on, it’s never where you left it,” he points out. “So there’s a bit of work to do there.” But he adds that profound changes are also possible. If, for example, overseas students “decide that, in fact, they’re just going to stay closer to home because this is too big of a risk,” says Walmsley, “fundamentally that changes the face of higher education—not only in the U.K., but globally. Then remote education comes into its own.”

The ultimate impact, Ramponi notes, will depend largely on how long the current shutdown lasts—something that currently seems almost impossible to tell. “If, after one or two months, we can’t go back to normal life, then it becomes real tough” to move forward with labs offline, she says. “Photonics has a lot of modeling behind it, but it’s an experimental science and a hardware technology.”

Yet Ramponi stresses that, ultimately, keeping one’s eye on life after the crisis is essential.

“While of course we need to try to deal with contingencies, we also need to plan for the future—to have a perspective on how we will start working again when this situation ends,” she says. “This motivates people, and gives them the idea, ‘Okay; we’re in a shutdown, but it’s temporary, and we are already planning about how to start up again.’ I think this is the most important thing we have to do.”