A predatory Actinostola sea anemone, perched on a lava pillar on the East Pacific Rise at around 2.5-km depth, as captured by the recently upgraded deep-sea imaging system on the submersible Alvin. [McDermott, Fornari, Barreyre, Parnell-Turner, AT50-21, WHOI-NDSF, NSF, MISO Facility, ©WHOI, 2024 / Originally in A. Steiner et al. J. Ocean Technol. 19(3), 64 (2024); used with permission / Organism ID by T. Shank]

A predatory Actinostola sea anemone, perched on a lava pillar on the East Pacific Rise at around 2.5-km depth, as captured by the recently upgraded deep-sea imaging system on the submersible Alvin. [McDermott, Fornari, Barreyre, Parnell-Turner, AT50-21, WHOI-NDSF, NSF, MISO Facility, ©WHOI, 2024 / Originally in A. Steiner et al. J. Ocean Technol. 19(3), 64 (2024); used with permission / Organism ID by T. Shank]

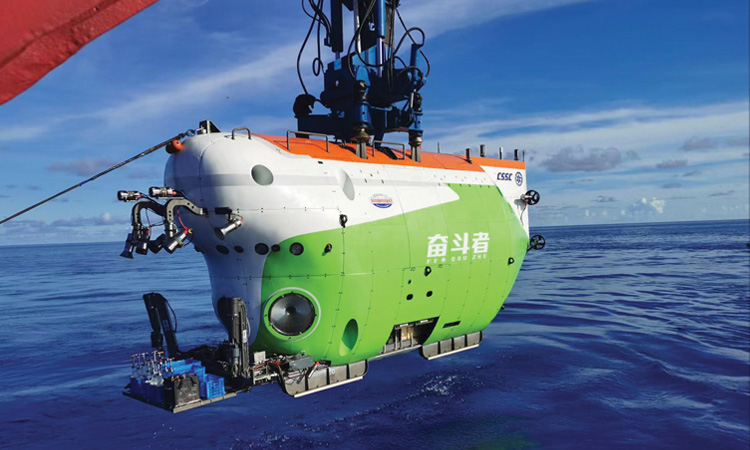

In July 2024, a team from China’s Institute of Deep-Sea Science and Engineering made an extraordinary discovery nearly 10 km below the Pacific Ocean’s surface, in the Kuril-Kamchatka Trench: an environment teeming with life. Riding in the deep-ocean submersible Fendouzhe, the researchers encountered forests of tube worms and bivalves that survive and thrive in the trench’s dark, freezing depths not by photosynthesis but by “chemosynthesis,” tapping fluids rich in methane released by muddy deposited organics.

In a paper published in Nature in July 2025, the scientists called the find the deepest and most extensive chemosynthetic community yet observed. And they suggested that its methane-rich environment could cast new light on the deep sea’s complex carbon dynamics—an important variable in global climate change.

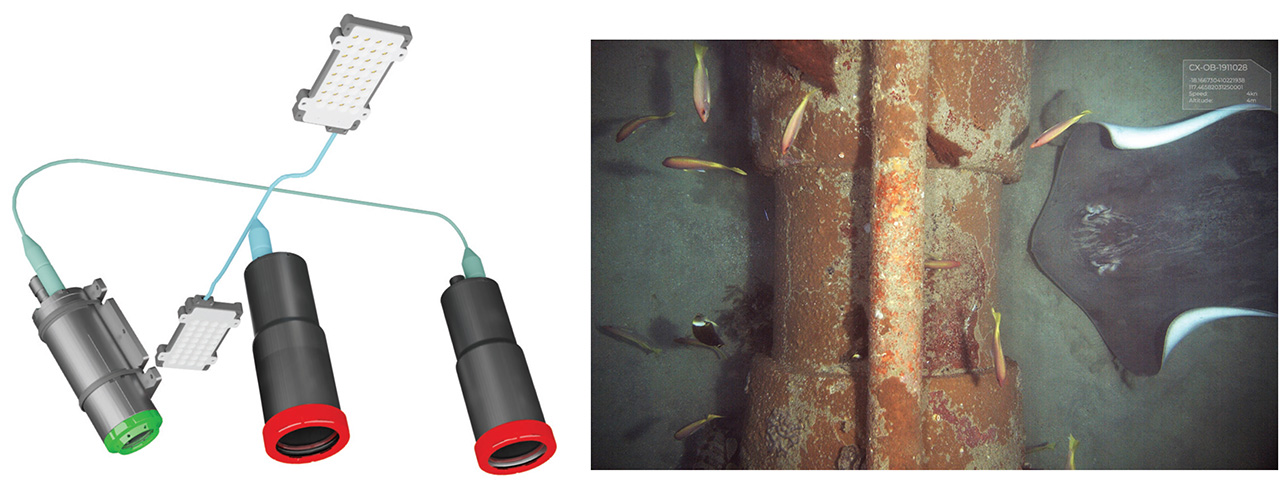

The Chinese research submersible Fendouzhe is equipped with deep-sea cameras by the Norwegian supplier Imenco that are rated to a depth of 11 km. [Xinhua]

The Chinese research submersible Fendouzhe is equipped with deep-sea cameras by the Norwegian supplier Imenco that are rated to a depth of 11 km. [Xinhua]

It’s not surprising that the ancient ocean floor can still yield up new things. According to a Science Advances study published in May 2025, less than 0.001% of the global seafloor has been visually observed (excluding proprietary commercial data). Moreover, the authors maintain, even that tiny sample is “incredibly biased,” with most observations clustered around specific zones repeatedly surveyed by a handful of wealthy countries, institutions and companies.

The ocean, covering two-thirds of Earth’s surface, is the planet’s biggest, richest ecosystem and a key regulator of global climate.

That matters, because the ocean, covering two-thirds of Earth’s surface, is the planet’s biggest, richest ecosystem and a key regulator of global climate. Further, marine communities are uniquely vulnerable to the temperature swings, acidification and changes to ocean circulation that climate change will bring. Katy Croff Bell of the Ocean Discovery League, Saunderstown, USA, who led the Science Advances study, believes the limited visual coverage of the seafloor is a major stumbling block to quantifying those threats. “It’s really difficult to understand how the climate is changing and impacting [ocean] communities,” Bell says, “when you don’t even have a baseline to start with.”

Building that better baseline will require a comprehensive visual picture of the seafloor. That means a worldwide scientific effort, involving crewed research submersibles like the Fendouzhe and fleets of remotely operated and autonomous robotic craft—all equipped with optics and lighting specially modded for the harsh conditions in the deep sea. The topic, like the ocean itself, is vast; here we look at just a few efforts toward a better view.

Deep-diving observatories

Much has been learned about the seafloor through remote sensing, including bathymetry (depth measurements) via sonar and synthetic aperture radar, and even, for water depths of a few tens of meters, airborne lidar scanning. Yet, in their Science Advances study, Bell and her colleagues stress the importance of direct visual imaging for biological and geological information, and for “ground-truthing” observations from remote sensing. For depths greater than 200 m, the only way to get that visual view is to go down and take a look.

Researchers perform those visual surveys using a variety of submersibles launched from research vessels (RVs) at the sea surface. Some submersibles are human-occupied vehicles (HOVs), such as the Fendouzhe, that take a handful of observers down for short periods. Others are remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) tethered to the RV by electrical and fiber optic cables. A third category includes autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), untethered, self-guiding robotic craft that can cruise the seabed for hours to a few days before being retrieved for data download and battery recharge. And some missions use passive “towsleds” dragged along by cables attached to the surface RV.

While dives to the ocean’s deepest reaches, 10 km or more below the surface, grab headlines, roughly 97% of the seafloor is at depths of 6000 m or less. That limit lay behind recent upgrades to the venerable HOV Alvin, a US Navy–owned craft operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Woods Hole, USA, that has undertaken more than 5100 dives in the past six decades. The upgrades completed in 2021 boosted the craft’s maximum dive depth from 4000 m to 6500 m, giving scientists direct access to all but 1% of the ocean floor.

Alvin’s new capabilities are complemented by WHOI’s workhorse ROV Jason, also rated to 6500 m, and its Sentry AUV, which can submerge to up to 6000 m. Together, the three submersibles form the core of the National Deep Submergence Facility (NDSF) at WHOI, sponsored by the US National Science Foundation (NSF), the Office of Naval Research and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A number of other institutions worldwide maintain similar research fleets. And private companies are also key players, especially in the AUV arena.

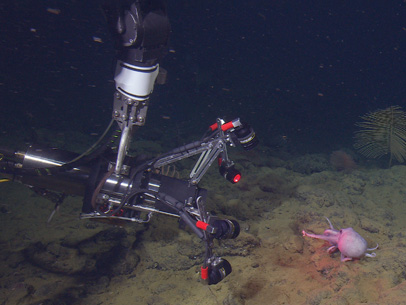

MBARI’s EyeRIS light-field camera studies an octopus in its natural environment. [© 2022 MBARI]

MBARI’s EyeRIS light-field camera studies an octopus in its natural environment. [© 2022 MBARI]

In an octopus’s garden

The Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in Moss Landing, USA, is one of several institutions worldwide operating fleets of research submersibles. It’s also developed an array of instruments and sensors customized for the deep sea. Some of those goodies come from MBARI’s Bioinspiration Lab, which, according to MBARI engineer Paul Roberts, focuses largely on fashioning structured-illumination-based imaging tools to accelerate discovery of natural ocean processes—and, in turn, inspire new technologies.

One recent fruit of the lab’s work is EyeRIS, a plenoptic camera that uses multiple perspectives in the same shot to capture both spatial and angular information, from which 3D data can be computationally extracted. At the heart of the setup is a light-field camera from the German company Raytrix equipped with an array of tens of thousands of microlenses, each oriented at slightly different angles, in front of the main camera lens. MBARI mounted that camera inside a “pretty standard” titanium housing rated to 4-km depth, Roberts says, and paired it up with illumination consisting of six DSPL SeaLite modules.

In a Nature paper published in August 2025, an MBARI team reported using this camera in a detailed, quantitative study of the 3D biomechanics of a deep-sea octopus in its natural habitat, the recently discovered “Octopus Garden” off the California coast. The team thinks the findings have “implications for the design of future octopus-inspired robots.” To Roberts, the project exemplifies “the really cool part” of the technology he helped develop: the ability to “make quantitative measurements of how this very complex organism is moving around in its natural environment, when that’s 3000 m underwater.”

Hostile environment

The most basic optical systems riding on these subsea platforms are visible-light cameras and an accompanying illumination package. But even at “only” 6000-m depths, those optics confront insults undreamed of on Earth’s surface—most obviously the pressure from the kilometers of water overhead.

Carlos López-Mariscal, senior optical scientist at Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland, notes that every 10-m depth increase in salt water adds an atmosphere of pressure. “You do the math,” he says. Beyond the shallowest depths, “things that are solid up here … just crumble like paper.” The marine environment is also rife with threats of corrosion and humidity to sensitive components, as well as a need to pack along batteries providing “as much power in the smallest package you can” in that hostile, remote environment.

Then come the significant optical challenges of imaging through salt water near the seafloor. The ocean’s aphotic zone, beyond 1 km deep, is inconceivably, permanently dark, so artificial illumination must come along for the ride. Light scattering is a vexing problem, and seawater is a potent absorber particularly at long wavelengths, leaving uncorrected pictures with an unrealistic bluish-green hue. As a result, “even if you have your light sources ready for their purpose,” López-Mariscal says, “you need to get really close.” For most visual surveys, that means the submersible must “fly” only a few meters above the seafloor.

Finally, deep-seafloor imaging rests on factors well beyond cameras and lighting. Daniel Fornari, a marine geologist and emeritus research scholar at WHOI, stresses that the resolution at which you can study features “has a big role in how well you can understand them.” And resolution gains have, over the years, relied on improvements not just in optics but in precisely tracking the vehicle’s position, its attitude in the water and its underwater navigation. “You had to do all of these things at the same time,” Fornari says.

Upgrading Alvin’s eyes

In his quest to “do field geology at the bottom of the ocean,” Fornari has been tackling the practical and optical challenges of deep-seafloor imaging since the 1980s. Over the past 25 years, he has also developed WHOI’s Multidisciplinary Instrumentation in Support of Oceanography (MISO) facility. Funded by the US National Science Foundation, MISO specializes in creating imaging and other tools for seafloor surveys and in combining seafloor sampling with concurrent imaging, both for WHOI NDSF vehicles like Alvin and Jason and, more broadly, for the US academic fleet.

For such submersibles, the imaging solution commonly involves putting a top-quality consumer or professional camera inside a pressure housing that can stand more than 600 atmospheres at depth. Since the early 2000s, Fornari has partnered with several industry firms, including DeepSea Power & Light (DSPL), San Diego, USA, and EP Oceanographic, Pocasset, USA, to create such hybrid systems.

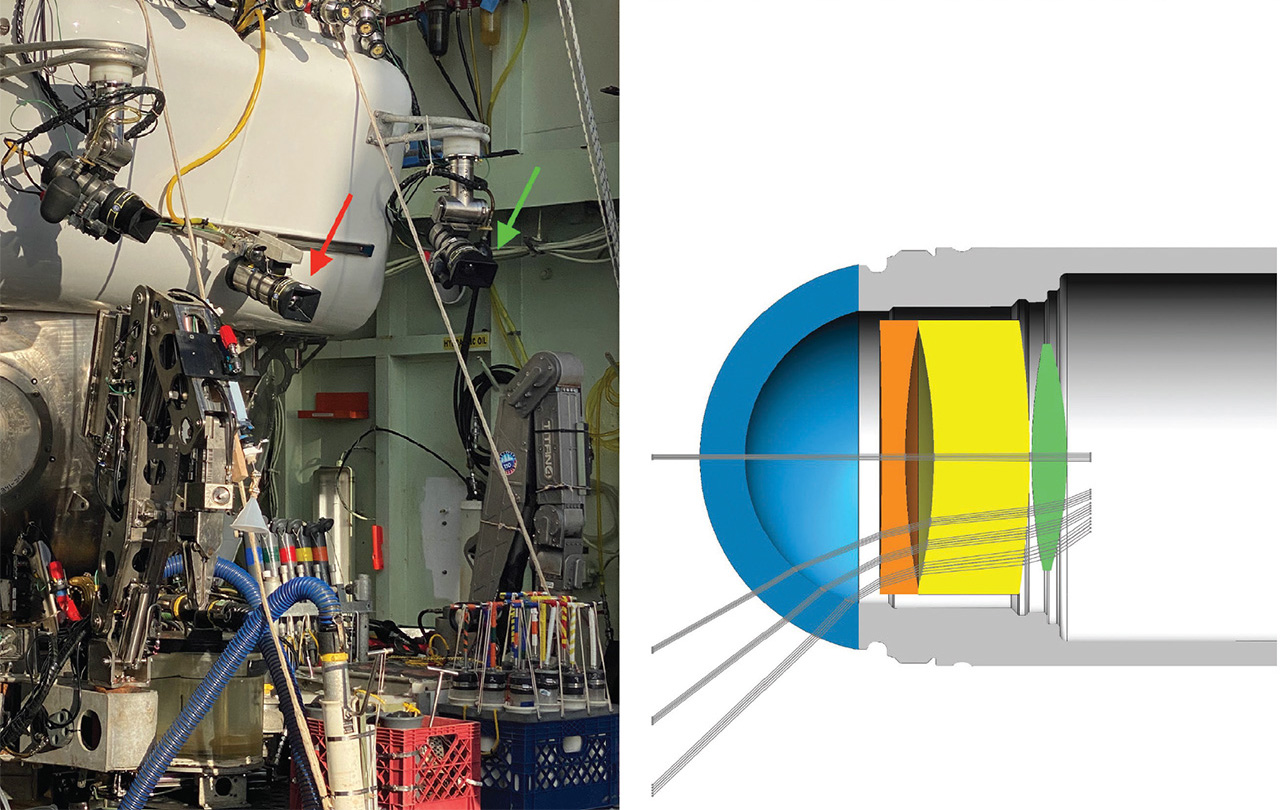

A hemispheric dome port for incoming light is the configuration of choice for the deep sea, mainly for the dome’s inherent mechanical pressure tolerance and for certain advantages of spherical optics.

An important early DSPL contribution, Fornari says, lay in developing water-corrected dome optics for subsea pressure housings that were matched to the camera lens inside. As Aaron Steiner, DSPL’s director of engineering, explains, a hemispheric dome port for incoming light is the configuration of choice for the deep sea, mainly for the dome’s inherent mechanical pressure tolerance and for certain advantages of spherical optics. But the dome design introduces chromatic aberrations, pincushion distortions and field curvature. In the early 2000s, DSPL undertook the painstaking, iterative process of designing corrective optics to flatten the field projected onto the camera image sensor. The solution, Steiner notes, was so robust that it still features in the latest MISO cameras.

[Enlarge image]Left: The Alvin submersible, configured for a June 2024 dive into the Aleutian Trench (around 5 km deep), including recently upgraded camera systems in DSPL housings rated to 11-km depths (arrows). Right: Ray-tracing diagram showing refracted light through the dome port of the pressure housing, and custom optics to widen the field and correct for field curvature. [T. Shank, WHOI [left], DeepSea Power & Light [right] / Originally in A. Steiner et al. J. Ocean Technol. 19(3), 64 (2024); used with permission]

[Enlarge image]Left: The Alvin submersible, configured for a June 2024 dive into the Aleutian Trench (around 5 km deep), including recently upgraded camera systems in DSPL housings rated to 11-km depths (arrows). Right: Ray-tracing diagram showing refracted light through the dome port of the pressure housing, and custom optics to widen the field and correct for field curvature. [T. Shank, WHOI [left], DeepSea Power & Light [right] / Originally in A. Steiner et al. J. Ocean Technol. 19(3), 64 (2024); used with permission]

Since 2015, the MISO team has focused on adapting GoPro HERO consumer cameras into the DSPL-designed and -built pressure housings. In sync with Alvin’s recent upgrades, the team jumped from a workhorse system built on GoPro’s HERO4 model, capable of capturing 10-Mpx still images and 4K motion video at 24-fps frame rates, to the GoPro HERO11 model, which boosted still-image resolution to 27 Mpx and provides 5.3K cinematic video acquisition at 30 fps. The system is now offered in both 6-km-depth-rated and 11-km-rated DSPL titanium housings—providing access, in principle, to the entire seafloor.

While Fornari says he doesn’t “do brain surgery on these cameras,” modifying consumer GoPro devices for deep-sea pressure housings has still taken some ingenuity. This has included replacing the GoPro’s built-in fisheye lens with a 5.4-mm non-distortion lens (with a fixed-focus design that provides depth-of-field from 0.5 m to infinity), and adjusting the camera to the housing’s internal geometry to align precisely with the corrective optics behind the dome port.

Eelume’s Ecotone Hyperspectral Ocean Vision system. [Eelume]

Eelume’s Ecotone Hyperspectral Ocean Vision system. [Eelume]

Casting light on seafloor composition

Recent years have seen increasing interest in mining of the deep seafloor—a prospect that’s steeped in controversy. Advocates argue that such mining could yield new sources of rare metals crucial for green energy. Opponents warn that it could cause irreparable harm to fragile ocean ecosystems. Researchers are looking at how a few optical and photonic techniques beyond reflected-light photography could illuminate these issues by helping to map out the seafloor’s chemical and mineral composition.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI)—in which a full reflectance spectrum is collected for each image pixel, resulting in a 3D “data cube” combining spatial and spectral information—has the potential to provide high-resolution mapping of compositional variations along the deep seafloor. As with all visible-light imaging in the deep, dark ocean, HSI requires that the imager be accompanied by a bright broadband light source and that it operate very close to the seafloor, given seawater’s attenuation of long-wavelength light.

In 2018, a team led by scientists from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim, Norway, used ROV-based HSI both to map manganese nodule deposits at depths greater than 4 km and to help classify marine organisms based on “optical fingerprints.” More recently, researchers in a variety of countries have developed increasingly sophisticated computational deep-learning approaches to sort through massive HSI data cubes.

Commercial players are also in on the act. The NTNU spinoff Ecotone, acquired in May 2025 by the Norwegian AUV supplier Eelume, offers integrated HSI systems combining imager, lighting, software and accessories. And the Bremen, Germany–based startup PlanBlue hopes to combine underwater HSI and RGB imaging, artificial intelligence and precise georeferencing to measure a range of environmental variables related to seafloor health.

Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) could also provide data on the deep seafloor’s chemical composition. In LIBS, a tightly focused, high-intensity laser blasts a sample into a plume of plasma; as the plasma cools, it emits light with spectral peaks corresponding to specific chemical elements in the sample. Rapid plasma quenching and pressure effects in the deep sea can significantly degrade signal quality, but researchers have proposed workarounds to these problems via setups that use double-pulse techniques or employ relatively long-duration single pulses.

In 2020, a team led by scientists from the University of Tokyo, Japan, and the University of Southampton, UK, used a long-pulse LIBS setup, combined with multivariable analysis, to map hydrothermal deposits of copper, lead and zinc 1000 m below the sea surface. The same year, a separate team, from Laser Zentrum in Hannover, Germany, reported, in a laboratory study, a double-pulse LIBS system that could operate at water pressures as high as 600 atmospheres, corresponding to ocean depths of 6000 m.

Lighting things up

Illuminating the otherwise pitch-dark deep seafloor is every bit as important as the imaging system. “You can have the best damn camera that you want,” Fornari says, “and if you don’t improve your lighting, you’re cutting off your nose to spite your face.” While deep-sea strobes, initially developed in the 1950s by Harold “Doc” Edgerton of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, were long standard equipment, they have been largely—but, Fornari notes, not entirely—supplanted by more compact, tunable and power-efficient LEDs.

The switch to LED lighting for deep-sea studies brought enormous power-efficiency gains for undersea work. But, as DSPL’s Steiner points out, it also brought a much less solar color quality, with a big peak in blue wavelengths. That’s a bad fit with imaging in seawater, which strongly absorbs longer-wavelength energy, giving the imager a very poor return of reflected light on the redder end of the spectrum. Thus, Steiner says, improving the color quality of the submersible’s LED lighting was a big part of providing “world-class imaging capabilities” in the recent upgrades to WHOI’s Alvin.

In recent years, DSPL has worked with its primary LED manufacturing partner, Cree LED, to raise the color-rendering index (CRI) of its deep-sea-rated SeaLites from 70 to above 90—corresponding to a spectrum much closer to daylight, which has a CRI of 100. The difference is “stark if you see it in person,” says Steiner, and brings a much healthier dose of red light back to the digital sensors. The Alvin now uses exclusively DSPL LED lights rated to 11,000-m depths.

Since August 2022, the upgraded MISO GoPro HERO11 cameras and lighting have been used on more than 100 Alvin dives and, in Fornari’s view, have produced “some of the best deep-sea images ever.” He describes the system’s underwater 0.5-m-to-infinity depth-of-field as “mind blowing,” and notes the “huge” impact of the jump from 4K video with the HERO4 to 5.3K with the HERO11. Meanwhile, the bright, high-spectral-quality illumination, coupled with the ever-improving GoPro image-handling algorithms, means that the video images, even through seawater, require little or no color correction. “The camera does all the work for you,” he says. “Basically, the images are superb just the way they are.”

Beyond image quality, the GoPro cameras have another advantage: endurance. Steiner says that putting the compact GoPro line in the relatively capacious DSPL housing allowed the team to “stuff a really large battery in there.” That lets the camera operate as a “set it and forget it” system, enabling “quiescent” imaging by multiple, differently oriented cameras with no work from the scientists on the submersible across the entire dive. “From an efficiency point of view, that’s huge,” says Fornari.

A “Lighthouse” below the waves

Like WHOI’s MISO program, the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel in Germany uses a range of cameras packed in custom, dome-port-enabled pressure housings. But Tom Kwasnitschka, the undersea volcanologist who heads up a deep-sea cameras and lighting unit at GEOMAR, says that even with corrective optics, the dome ports are typically not well optimized for precise photogrammetric scans. He describes such scans, using ROVs or AUVs, as “the equivalent of a spy plane on the seafloor,” allowing full, photorealistic, 3D digital models of subsea territory, “down to the millimeter scale.”

Although small-area scans have been demonstrated for decades, scaling things up for exploration and monitoring of large zones has been tough, Kwasnitschka says, due to both the optical limitations of existing cameras and the challenges of precise undersea navigation and positioning.

Typically these hurdles are addressed, imperfectly, by software algorithms, but Kwasnitschka wanted to see if, for the optical side at least, a hardware solution was possible. So he “took a leap of faith” and contacted Jena, Germany–based Zeiss Group. In what he calls a “cosmic coincidence,” he found that the company’s R&D department was looking at developing just such a product.

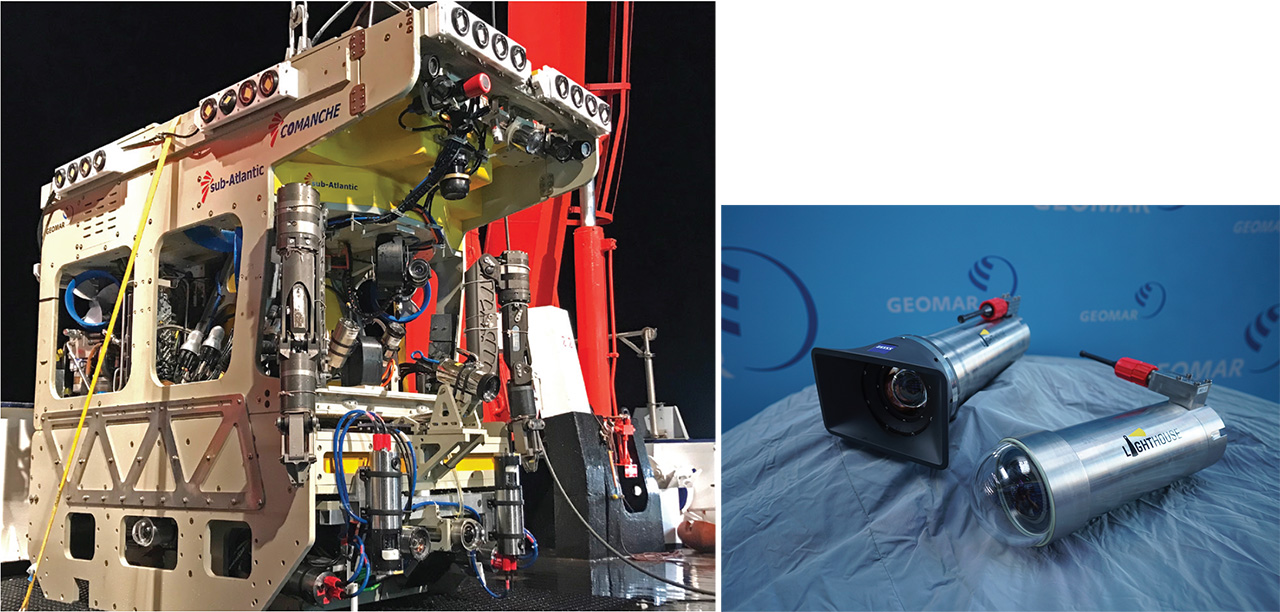

Zeiss and GEOMAR collaborated on a full camera design that dispensed with a dome port and put the camera lens in direct contact with seawater. The lens—with a 100° field of view, and with corrections for field curvature and chromatic aberration built in—was designed, in Kwasnitschka’s words, to be “squished” within certain software-correctable tolerances as pressure increases (to a working depth of 6000 m and a maximum rated depth of 9000 m). The deep-sea lens, trade-named DUW Distagon by Zeiss, was then packaged into a custom titanium housing, along with a bespoke machine-vision image sensor, electronics and battery. Putting the lens in contact with seawater eliminates refractive effects and other disadvantages of some dome ports, providing what Kwasnitschka describes as “an aerial camera for the deep sea” with quality “comparable to professional photography on land.”

[Enlarge image]Left: GEOMAR’s “Lighthouse”—which combines a new cinema-quality camera co-developed with Carl Zeiss, additional cameras, high-intensity LED strobes, acoustic sensors and laser ranging—mounted on the ROV Phoca for a mission in Sogn Fjord, Norway. Right: Cameras of the Lighthouse system. [T. Kwasnitschka, GEOMAR]

[Enlarge image]Left: GEOMAR’s “Lighthouse”—which combines a new cinema-quality camera co-developed with Carl Zeiss, additional cameras, high-intensity LED strobes, acoustic sensors and laser ranging—mounted on the ROV Phoca for a mission in Sogn Fjord, Norway. Right: Cameras of the Lighthouse system. [T. Kwasnitschka, GEOMAR]

Kwasnitschka’s team used those capabilities to construct a photogrammetry-optimized ROV system that aimed to create a “Google Street View car for the abyss.” The Helmholtz Association–funded project, called Lighthouse, combined the Zeiss–GEOMAR seafloor-imaging camera with additional cameras for situational awareness for the ROV operator, acoustic sensors for topography, line-structured-light laser scanners for ranging, and “a corner of a football stadium worth” of power-efficient strobed LED lights. Interestingly, Kwasnitschka says, the team no longer uses the laser ranging, as the super-crisp Zeiss-based photogrammetry plus acoustically determined topography provide superior results in practical deployments.

Operating at 2.5–4 m above the seafloor, the Lighthouse ROV collects two high-resolution still images per second, as well as 4K video at 30 fps, in a photogrammetry-friendly square format. The system, he says, can produce “acre-sized, 4-mm-resolution 3D seafloor models.” Since its successful first demo in 2022, elements of the Lighthouse platform have been deployed by GEOMAR, WHOI, the Schmidt Ocean Institute and even the BBC.

AUVs allow the collection of thousands of useful measurements in a single mission. The vehicles are also unsupervised, allowing them to independently collect data, alone or in multi-AUV groups.

Going autonomous

The visual-imaging advances of the past decade have dramatically sharpened the view achievable in deep-sea HOVs and ROVs. But these missions, by design, are focused efforts covering only a tiny area of seafloor, with the submersible often moving at a stately pace—typically, for the Alvin, around 0.5 nautical miles per hour (knots). Getting a broader picture of the undersampled global seafloor will thus likely hinge heavily on the third type of submersible: roving, robotic AUVs.

Victoria Preston, a roboticist and assistant professor at Olin College of Engineering, Needham, USA, believes that AUVs have “very unique superpowers” for deep-sea exploration. “An amazing part of an AUV,” she says, “is that I can put a sensor in the right place at the right time,” allowing the collection of thousands of useful measurements in a single mission. The vehicles are also unsupervised, she adds, allowing them to independently collect data, alone or in multi-AUV groups, while shipboard researchers focus on other tasks. “They work as a force multiplier for scientists when we go to sea,” Preston says.

These features enable deep-sea visual imaging on a scale previously out of reach. “We can create really large photomosaics using AUVs, which can be down days at a time now, which is really exciting,” Preston notes. And AUVs can also efficiently and independently survey a large area of seafloor multiple times over days, months or years, to provide a window on changes over time. “It’s opening new frontiers of questions for us to even ask.”

Tapping developments in industry

While institutions like WHOI and GEOMAR have their own AUVs tailored to deep-sea research, the industrial and defense applications of these robotic craft have also spawned a vast commercial market. A report published in June 2025 by BCC Research estimated the global AUV market at US$2.4 billion. They’ve been used for everything from regular surveillance of subsea pipelines and cables to locating downed aircraft and studying the wreck of the Titanic.

The global AUV market is estimated at US$2.4 billion. They’ve been used for everything from surveillance of subsea pipelines and cables to locating downed aircraft and studying the wreck of the Titanic.

Adrian Boyle—the founder and CEO of Cathx Ocean, Naas, Ireland, which develops and markets AI-empowered imaging systems for AUVs primarily for industrial and defense applications—believes the technologies devised for these markets have much to offer the academic side as well. “I think there’s a real opportunity,” he says, “to shift the needle” in how quickly the seafloor can be imaged, and how quickly critical information can be extracted from the image data, for large-scale environmental and other studies.

A physicist by training, Boyle cut his teeth on optical switching for 10-Gb communications, and says his brain is “wired to think in time sequences.” That mindset shows in Cathx’s hardware offerings. An example is the company’s Hunter II product, which combines an optical camera, a 510–530-nm laser and a laser sensor—all rated to up to 6000-m depths—with a pulsed LED array that can pump out up to 400,000 lumens of light on the camera’s field of view. The system is installed in the hull of the AUV along with high-capacity, GPU-level data-processing capabilities packaged in small form factors carefully tuned for underwater use.

[Enlarge image]Left: Cathx Ocean’s Hunter II system includes a 510–530-nm laser, an optical camera, a laser camera and banks of bright pulsed LEDs. Right: Hunter II image of a section of pipeline, taken 4 m above the seafloor in an AUV traveling at a relatively fast 4 knots, shows substantial detail without motion blur. [Cathx Ocean]

[Enlarge image]Left: Cathx Ocean’s Hunter II system includes a 510–530-nm laser, an optical camera, a laser camera and banks of bright pulsed LEDs. Right: Hunter II image of a section of pipeline, taken 4 m above the seafloor in an AUV traveling at a relatively fast 4 knots, shows substantial detail without motion blur. [Cathx Ocean]

On a typical mission, an AUV equipped with the Hunter II will “fly” 5–10 m above the ocean floor at speeds of up to 5 knots. The powerful strobes are pulsed for a millisecond at a time, three to seven times per second, to create a sequence of sharp, overlapping, georeferenced optical images. Between strobe flashes, the laser scans the seafloor at a rate of 60 sweeps per second, creating a 7-m-wide swath of laser light. The laser returns provide 3D range information at a resolution of a few millimeters, according to Cathx.

Those high-res, georeferenced 2D and 3D data give the company’s software something to work with. “If we know how far away we are from everything on the seafloor and we know the size of everything, we can actually start to apply physics,” Boyle says. That includes calculating color correction based on wavelength and distance under the Beer-Lambert law, and mapping the 2D color pixels from the optical image onto the laser pixels to build large-scale, 3D photomosaics of the seafloor.

While Cathx’s products were designed for industrial and defense applications, Boyle stresses that the company’s platform and “data agent infrastructure” are largely application- and sensor-agnostic, and could be relevant to problems in the scientific community such as visual imaging and tracking changes in sparse communities of organisms across large seafloor areas. Such applications, he says, will require considerable coordination and alignment within the scientific community. But “if it’s done the right way,” he thinks, “change detection in real time, as a means to address the challenge of getting the most important information from vast data sets quickly, is going to be possible in the next three years.”

A matter of cost

Katy Croff Bell, the lead author of the Science Advances study, likewise believes that AUVs will prove crucial in boosting visual coverage of the seafloor. But the biggest nut to crack will lie in making seafloor studies generally less expensive. “Bringing down the cost by an order of magnitude or two is what really needs to happen” to put these efforts within reach for a wider variety of countries and communities, Bell says. And another key is making the technologies accessible, so that “you don’t need to have a Ph.D. in engineering to be able to use it.”

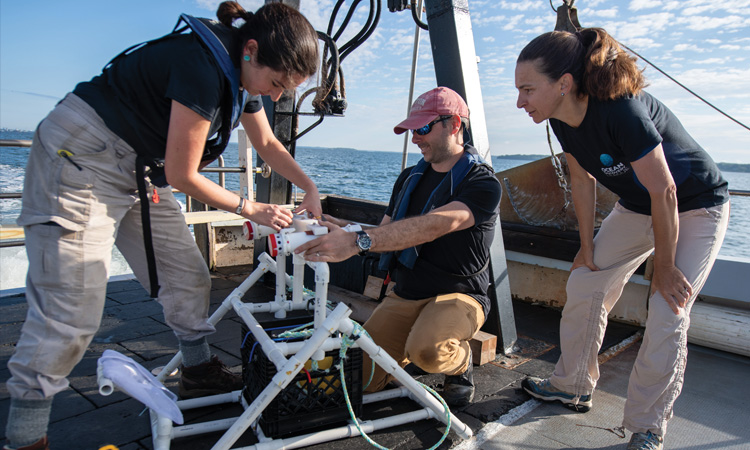

Katy Croff Bell (right), with colleagues Jessica Sandoval and Brian Kennedy, on a 2023 test deployment of the low-cost Maka Niu seafloor-imaging system off the coast of Rhode Island. [Ocean Discovery League / S. Poulton]

Katy Croff Bell (right), with colleagues Jessica Sandoval and Brian Kennedy, on a 2023 test deployment of the low-cost Maka Niu seafloor-imaging system off the coast of Rhode Island. [Ocean Discovery League / S. Poulton]

Bell herself is investigating tools to address both issues. In a 2022 study, she and an international group of deep-sea researchers unveiled Maka Niu, a system that packs a Raspberry Pi single-board computer, camera, wireless communications, battery and electronics into a 1,500-m-depth-rated pressure housing made of stock and 3D-printed plastic parts. The total cost: roughly US$1000. Bell is now working with academic and industry partners to develop a new system rated to 6000 m, and ultimately commercializing it as the Deep Ocean Research and Imaging System (DORIS).

As costs come down and accessibility goes up, both top-down academic efforts and bottom-up initiatives such as DORIS will, in Bell’s view, help to foster what she and her coauthors call “more equitable collection of global deep-sea data.” Such a framework, she thinks, will be crucial in providing a richer view of climate change and its impacts. And better, more expansive visual imaging could also have a side benefit: reminding people around the world—in a way not captured by dry statistics—why they should care about endangered, fragile ocean environments in the first place.

“You can show somebody a table, or a list of fish that you’ve seen,” says Bell. “Or you can show them a video of this amazing seascape of a deep-sea coral reef with fish and crabs and all these things. It’s just so much more compelling to be able to build that connection for people.”

Stewart Wills is a science and technology writer based in Silver Spring, MD, USA.

For references and resources, visit: optica-opn.org/link/seafloor.