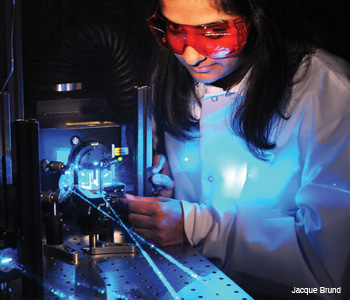

Ulka Patel of CREOL conducts research in lasers.

Ulka Patel of CREOL conducts research in lasers.

On the side of a brick building on a modern, well-groomed campus, a diffraction-grating sculpture breaks the blazing Florida sunshine into its shimmering spectrum. The pure colors, however, only hint at the brilliance of the work going on inside.

The institution within that building—CREOL, the College of Optics and Photonics at the University of Central Florida in Orlando—is marking the 25th anniversary of its founding in 1987. From its beginnings as a specialized center with temporary space and faculty appointed to scattered departments, CREOL has become a full-fledged college within one of the largest universities in the United States. Indeed, it was the first college of optics in America. It retains the CREOL acronym in homage to its roots as the Center for Research in Electro-Optics and Lasers.

Today, CREOL encompasses a next-generation laser physics center, the Townes Laser Institute and the Florida Photonics Center of Excellence—a state-funded program to develop optical technologies in areas of rapid market growth. The college has an incubator for fledgling companies and a solid track record of placing its alumni in the optics industry. Research spans the spectrum from terahertz frequencies to X-rays. Faculty members hold degrees in various subjects—chemistry and materials science as well as physics and engineering—but they work together in a tight-knit, collegial environment.

The beginning: A caravan from Texas

In the early 1980s, then-governor Bob Graham (D-Fla.) convened a group of business leaders to figure out how to attract more non-agricultural, high-paying jobs to central Florida. Since the area already had a toehold in the nascent optics industry, the idea for a research center was born, said M.J. Soileau, CREOL’s founding director.

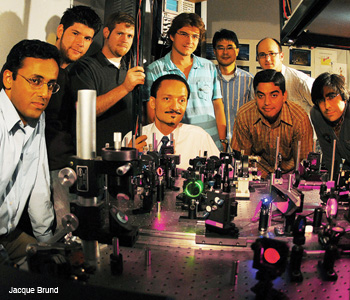

Peter Delfyett (center) in his CREOL lab.

Peter Delfyett (center) in his CREOL lab.

|

In 1986, the Florida legislature appropriated $1.5 million annually to launch the center at the University of Central Florida (UCF), a young institution in a city better known for tourism than higher education. UCF had awarded its first degrees only in 1970, and by the mid-1980s it had about 17,000 students across all departments.

Meanwhile, optical scientists at the University of North Texas had not been making as much progress in establishing a major research center as they had hoped. They looked at what other universities could give them; some held out five-year grants, but only UCF offered “$1.5 million forever,” says one of the scientists, Eric Van Stryland. Thus, the research group pulled up stakes and moved en masse to Florida. Soileau (now UCF’s vice president for research), future CREOL professors Van Stryland and David Hagan, seven graduate students and 42,000 pounds (19,000 kg) of lab equipment arrived to face an uncertain future.

“Everything was a challenge,” recalls Van Stryland, who eventually became the director of CREOL, the first dean of the College of Optics and Photonics and the 2006 OSA President. UCF was a young university without the infrastructure for traditional research, such as a system for recruiting and evaluating postdoctoral fellows. According to Van Stryland, Soileau had to bear the brunt of the financial battles with the university administration to get CREOL the human capital and physical infrastructure that it needed.

However, Van Stryland adds, the CREOL team could never have built such a center from scratch at an established university. “It was important that we could start with a university that didn’t know what they were doing so we could teach them how to do it right the first time,” he says. When the University of Arizona’s optics school became a college shortly after CREOL did in 2004, its director-turned-dean, James Wyant, thanked his counterparts at CREOL for their pioneering efforts, because Wyant had been trying to make such a change happen for a long time.

CREOL’s goal from the beginning was to be competitive with similar programs, according to Soileau. “We emulated, but not imitated, the Institute of Optics [at the University of Rochester] and the Optical Sciences Center [at the University of Arizona],” he says. “Both demonstrated that excellence could lead to good faculty and good students. We wanted to be mentioned in the same breath as these established programs.”

Education at CREOL

At its founding, CREOL had no authority to grant degrees. The earliest graduate students, who had arrived with Soileau and Van Stryland, officially received their degrees from the University of North Texas. In subsequent years, students who had done their research through CREOL graduated from other UCF departments and received a “certificate of appreciation” from the optical center. In January 1996, the Board of Regents approved the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in optical science and engineering, a few months before CREOL became a school within UCF.

The college now has about 129 graduate students, who take up to six core courses and a number of electives depending on the terminal degree. Three CREOL faculty members have won the highest campus-wide prize, the Pegasus Professor Award, for continued excellence in teaching and service—Peter J. Delfyett in 2001, Shin-Tson Wu in 2010 and Townes Laser Center director Martin C. Richardson in 2012. A professor with a joint appointment in optics and chemistry, Kevin Belfield, also won the award in 2012.

|

In addition to its robust graduate program, CREOL is awaiting final approval to add a bachelor’s degree in optics to its curriculum. It already hosts a Research Experience for Undergraduates program with U.S. National Science Foundation funding. By offering research experience to students from other campuses, this program is helping to to recruit potential graduate students to UCF. It impresses on all participants the importance of optics and photonics in modern science and engineering.

CREOL’s special agreement with two European universities, Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, Germany, and the University of Bordeaux in France, allows graduate students to receive dual master’s degrees. Clemson University in South Carolina is also part of the consortium, which is called the Atlantis-MILMI Program (for Master International in Laser, Materials science and Interaction). CREOL has a strong reputation with several Mexican universities, says optics professor Delfyett, a member of the technical committee for the next Latin America Optics and Photonics Conference in Brazil.

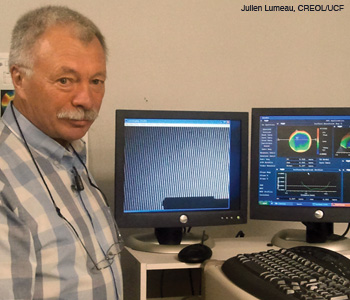

Leonid Glebov uses a Fizeau interferometer to measure flatness and optical homogeneity of optical elements.

Leonid Glebov uses a Fizeau interferometer to measure flatness and optical homogeneity of optical elements.

|

Four scientific societies, including OSA, have chapters at CREOL; in addition, an umbrella group called the CREOL Association for Optics Students coordinates interactions among the chapters and organizes educational outreach activities, including the annual CREOL open houses for the UCF community.

Scientific accomplishments

One measure of the scholarship of CREOL’s faculty is the national and international awards its members have received, according to Bahaa E.A. Saleh, who became the college’s dean in January 2009. For example, CREOL has notched three of OSA’s R.W. Wood Prizes for an outstanding discovery or invention: Van Stryland and CREOL alumnus Mansoor Sheik-Bahae (now at the University of New Mexico) in 2012, Demetrios N. Christodoulides in 2011 and George Stegeman (now an emeritus professor) in 2003.

Saleh groups CREOL’s diverse research tracks into five broad, interdependent categories.

Lasers. CREOL has invented several new materials for lasers. Today’s research group focuses on high-power lasers, especially for industrial uses like cutting and welding and developing new ceramics for these lasers, Saleh said. CREOL has recently established a new group developing attosecond lasers and ultra-precise frequency combs for use in metrology applications.

Optical fiber. CREOL is proud of its two fiber drawing towers, one for high temperatures and one for low. Not many universities have their own towers, according to Saleh. The college’s researchers are producing nanostructured fibers that incorporate multiple materials. They also study mid-infrared fiber lasers and next-generation coherent optical communication systems.

Semiconductors and integrated photonics. The “hot topics” in this area include quantum dots, nanostructures, photonic crystals and holographic optical elements. The college is well known for oxide-confined vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers, Saleh says. CREOL has a clean room for device fabrication, and it recently built a new laboratory dedicated to silicon photonics.

Nonlinear and quantum optics. Van Stryland and Sheik-Bahae invented the so-called Z-scan method for measuring higher orders of nonlinearities in optical materials. Another recent highly cited CREOL discovery, made by Demetri Christodoulides, is called the Airy beam: light that travels along curved lines in space. Several other researchers study nonlinear waveguides, quantum walks in integrated optics and plasmonics.

Imaging, sensing and display technologies. CREOL scientists are studying how to use polarization optics for biomedical imaging and nonlinear optics in microscopy for high-resolution applications. The college has a track record of developing liquid crystal display technology, including so-called blue-phase LCDs, with faster switching for smoother-looking image motion.

CREOL and industry

“The primary intellectual property that comes out of a university is the students—they get hired,” Soileau says. The hiring often leads to contracts between the laboratory and the company, and may culminate in technology transfer to business or even the founding of a new company.

CREOL’s business incubator operates in 10 different sites in and around Orlando, Soileau says. Sometimes a company gets big enough to “graduate” and move into its own facility, as professor Leonid Glebov’s OptiGrate Corp. is doing (see sidebar). Many have received Small Business Innovation Research or Small Business Technology Transfer grants from the U.S. federal government. “This is probably one of the best universities for the transition of technology from university to industry,” Glebov says.

Partnerships with universities also benefit companies, says Delfyett, who helped spin off Raydiance Inc. with technology invented under contract with the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Sometimes for-profit companies can contract with university faculty members to do cutting-edge research at a fraction of the overhead cost that it would take for the business to pursue that work.

“That kind of mix was the hope when we started, and that’s the kind of mix we have,” Soileau says.

Participants in CREOL’s 25th anniversary symposium in March 2012.

Participants in CREOL’s 25th anniversary symposium in March 2012.

Looking to the future

In the near future, CREOL leaders are looking forward to the start of the baccalaureate program “to graduate the next generation of optical engineers that is needed by industry,” Saleh says. UCF’s new medical school, only a few years old, should present the optics college with additional opportunities for joint research in biomedical imaging and laser surgery. The fiber optic drawing towers, also relatively new, should boost CREOL’s research in optical communications, according to Saleh.

Kathleen Richardson, who worked at CREOL in the 1990s and is returning to the college’s faculty this year, says she is excited that CREOL is diversifying into new research areas while maintaining its legacy strengths.

Many faculty and administrators speak of CREOL’s unique environment of camaraderie and collaboration. Glebov calls it “very well-organized freedom for research.” Van Stryland says that the highlight of his decade of serving as an administrator was the people he got to hire.

Certainly CREOL has come a long way from the days when the faculty lacked a dedicated building and the students had to lug around optical tables. Wherever the photonics industry goes in the next 25 years, CREOL is sure to play a major role.

|

Patricia Daukantas is a freelance writer specializing in optics and photonics.

Almost eight years after leaving CREOL, Kathleen Richardson is returning to find the college more academically diverse than ever.

Almost eight years after leaving CREOL, Kathleen Richardson is returning to find the college more academically diverse than ever.