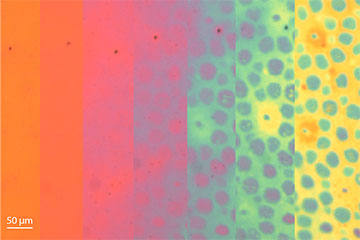

Time-lapse image of the evolution of color patterns in a soft photonic skin sample. [Image: Siddharth Doshi, Stanford University]

The octopus—a master of underwater disguise—can change both its coloration and its skin texture to match its surroundings. Nanostructures can create interference effects that alter the colors of artificial surfaces, but scientists have had trouble replicating the rapid changes in surface topography that aid the animal’s camouflaging.

The cephalopod’s concealment tactics have inspired scientists at a US university to devise an artificial photonic skin that changes its surface texture and color on demand (Nature, doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09948-2 ). The programmable polymer film swells and contracts in localized spots depending on exposure to irradiation from an electron beam and also changes colors based on microfluidic controls.

“Textures are crucial to the way we experience objects, both in how they look and how they feel,” said researcher Siddharth Doshi. “These animals can physically change their bodies at close to the micron scale, and now we can dynamically control the topography of a material—and the visual properties linked to it—at this same scale.”

Creating programmable textures

Team members at Stanford University fashioned their experimental thin film from a blend of a conductive polymer and a polystyrene sulfonate. To start with, the dry film was 90 nm thick.

Next, they hit the photonic skin with a narrow electron beam, then followed it by exposing the film to water. The radiation creates crosslinks between the molecules within the polymer, and these irradiated patches swell several hundred percent when the film is placed in water. Conversely, immersing the artificial skin in isopropyl alcohol or letting it dry out in air flattens out the surface. By manipulating the electron beam positioning and delivering varying doses of radiation, the researchers could trace out the Stanford logo and build a tiny model of El Capitan, a well-known rock formation at Yosemite National Park, USA.

And color patterns

The group then deposited a 20-nm-thick layer of gold on top of the polymer film. The metallic addition increased reflectance and enhanced the visibility of the topographic features to the naked eye. The area of the surface that reflects light within the collection solid angle of the eye appears brighter, while regions that redirects light outside the collection solid angle look darker. The visual appearance of texture comes from these alternating regions of dark and bright. .

Finally, the team sandwiched the polymer skin between two thin metallic layers. Together, the stack created Fabry-Pérot resonances that depended on the thickness of the polymer filling. Once again, exposure to water puffed up the polymer and changed the color of the device, with 90% of the evolution happening within 10 seconds.

Looking ahead

By combining both techniques into a multilayer device, the Stanford researchers found that they could independently manipulate both texture and color at the same time. Currently, they have to manually adjust the combination of water and solvent to achieve their desired effect, but in the future they hope to integrate a computer vision system that could automatically adjust the swelling levels. They predict that refinements of the new photonic film could find many applications ranging from camouflage to encryption to dynamic forms of visual art.

“Small changes in the properties of soft materials over micron distances are finally possible, which will open up all sorts of possibilities,” study author Nicholas Melosh said. “I think there are a lot of exciting things coming up.”