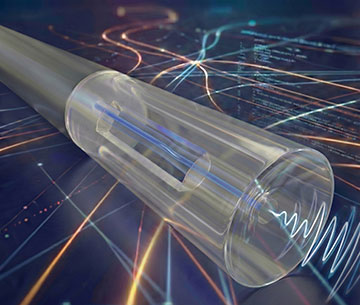

The hair-thin microphone detects sound waves via a tiny membrane and narrow beam sculpted inside a silica fiber, whose oscillations are converted to path-length variations of laser light entering the fiber. [Image: Xiaobei Zhang, Shanghai University]

Scientists in China have built a new kind of acoustic sensor housed entirely inside optical fiber that is able to pick up tiny sounds over a wide range of high frequencies (Opt. Express, doi: 10.1364/OE.582945). Having tested their device at temperatures of at least 1000°C, they reckon it is well suited to detecting the distinctive signals from electrical transformers that presage power outages.

Better diaphragm materials

High-voltage transformers are integral to the world’s power grids, making it vital that any signs of impending failure are picked up as they occur. The sound emitted by tiny sparks inside transformers is one such signal, but sensors that convert that acoustic energy directly into electricity are susceptible to heat and electrical interference. Fiber optic sensors in principle provide an attractive alternative, as they can be made resistant to high temperatures while being immune to interference.

Researchers have developed acoustic sensors based on a number of different types of interferometer, with Fabry-Perot devices offering significant flexibility in terms of design and choice of material. One promising option is a Fabry-Perot sensor employing a diaphragm, as this can be both compact and very sensitive. However, each of the diaphragm materials investigated to date has its drawbacks—polymers, for example, are a popular choice but fail to survive above 200°C, while graphene membranes, although extremely sensitive, are complicated to make.

In the latest work, Xiaobei Zhang and colleagues at Shanghai University, collaborating with researchers at the State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Research Institute in Nanjing, instead sculpted a Fabry-Perot sensor entirely from silica fiber. Their exceptionally slender microphone is capped by a very thin diaphragm attached to an extremely narrow fiber beam, which is connected to the fiber bulk. Any sound reaching the detector causes the diaphragm and beam to periodically contract and relax, inducing oscillations in both the beam’s length and refractive index that in turn alter the path length of laser light entering and then exiting the far end of the fiber.

Making and testing the microphone

The researchers made their microphone by first splicing together a single-mode fiber and a so-called grapefruit fiber, which contains large air holes periodically arranged around a central core. They cut the latter so it was 355 µm long—roughly the length of the desired fiber beam—and then capped this with another short piece of single-mode fiber that they polished down, creating a 4.3-µm-thick membrane (the diaphragm). Finally, they used a picosecond laser and hydrofluoric acid to sculpt the beam inside an open cavity within the grapefruit fiber.

Operating the furnace at more than 1000°C for up to an hour and 40 minutes, they found that the sensor continued to perform essentially as it had when operating at room temperature.

To put their device to the test, Zhang and coworkers subjected it and a standard reference acoustic sensor to sound waves produced by a signal generator. Feeding their microphone with laser light at a specific infrared wavelength, they measured its performance by directing its output to a photodetector and oscilloscope. Performing a Fourier transform on the time-domain signal, they were able to establish whether the acoustic vibrations encoded within the laser light matched those of the signal generator.

These tests, the scientists say, yielded excellent results. They found that the input and output frequencies matched precisely, that their microphone could cover the range 40 kHz-1.6 MHz, and that it could detect weak signals well beyond human capabilities (at 80 kHz). They also found that they could pick up sound waves coming from most angles in the plane of the detector.

What’s more, the researchers tested their fiber sensor after placing it in a furnace. Operating the furnace at more than 1000°C for up to an hour and 40 minutes, they found that the sensor continued to perform essentially as it had when operating at room temperature—its cavity length varying by no more than 50 nm in that time.

Potential applications

Zhang and colleagues maintain that their device’s wide frequency response makes it potentially well suited to a variety of applications aside from its use in transformers. The lower end of the scale, they say, lends itself to underwater detection and monitoring of structural health, while the higher frequencies would enable ultrasonic imaging and non-destructive testing, among other things.

They acknowledge that the microphone, still a laboratory prototype, is not yet suited to industrial-scale production. They say that to reach that stage, they plan to integrate acoustic metamaterials into the device as well as using additive and subtractive manufacturing to create robust, all-silica packaging for long-term use. They also note that the sensor’s small size opens up the possibility of building arrays of microphones, which, they say, would be even more sensitive and suited to a wider variety of applications than single devices.