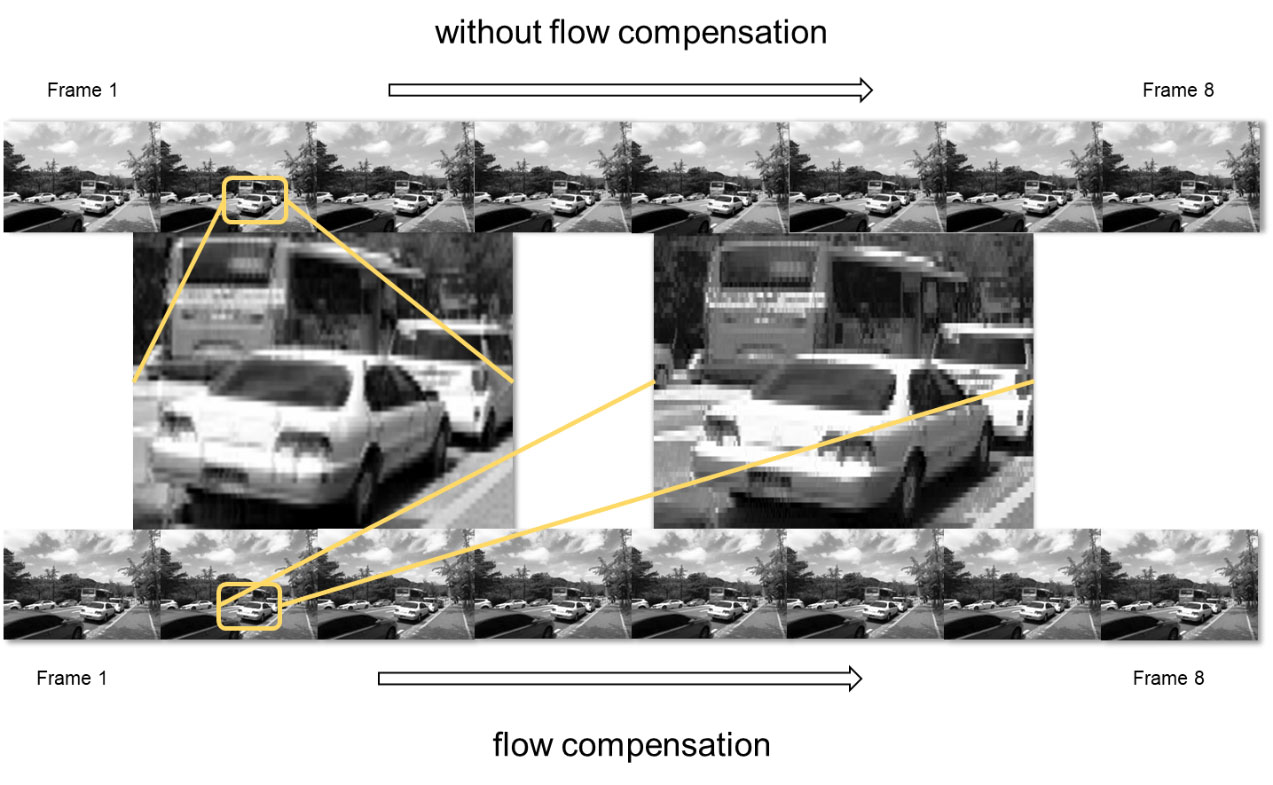

A new method aims to improve single-pixel imaging of moving scenes, in this case sharpening contours and reducing artifacts when recording the movement of buses and cars. [Image: Yuanjin Yu, Beijing Institute of Technology]

Scientists in China have devised a new method for limiting the blur and artifacts that usually dog single-pixel imaging (SPI) when it is used to record fast-moving scenes (Opt. Express, doi: 10.1364/OE.569103). They say that their scheme, which involves correcting the temporal alignment of pixel data within what is known as sliding-

window SPI, might potentially improve imaging in areas such as medical diagnostics and remote sensing.

Challenges of single-pixel imaging

While conventional imaging records scenes using many pixels arranged in spatial arrays, SPI instead uses a single pixel to generate a series of data points in time. Typically, this involves illuminating an object with light that has been encoded in a specific way by passing it through a spatial light modulator and then measuring the total intensity of the beam reflected or transmitted by the object. It is the correspondence between illumination patterns and their associated intensity levels that allows images to be reconstructed—with each still picture or frame in a video typically requiring thousands of data points.

SPI's robustness to scattering makes it well-suited to imaging through clouds or fog, improving the quality of some surveillance images. At the same time, its need for just a single-pixel detector makes it an attractive alternative to expensive infrared or terahertz imaging arrays. However, its reliance on sequential data acquisition makes it vulnerable to rapid movements of either the imaging platform or target, as any changes to the scene within a frame tend to blur or add artifacts to an image.

Researchers have proposed a number of ways to overcome these problems but struggle to increase frame rate without impairing image quality. Some have looked to improve the hardware, but that tends to increase costs and bulk. Others have tried to offset the effects of motion algorithmically, but the added complexity usually limits frame rate and can itself introduce artifacts.

Improving image quality

In the latest work, Yuanjin Yu of the Beijing Institute of Technology and colleagues have put forward a new approach that seeks to improve the quality of images from sliding-window SPI. Frame rates in a single-pixel setup are usually limited by the speed with which a spatial light modulator can switch from one configuration to the next. Digital micromirror devices, for example, can usually switch at up to 27 kHz.

In standard SPI, all the measurements needed to create a given frame are carried out before measurements for the next frame begin. Sliding-window SPI instead exploits a certain redundancy between measurements in successive frames, sampling frame-length numbers of measurements at staggered sub-frame intervals.

Sliding-window SPI instead exploits a certain redundancy between measurements in successive frames, sampling frame-length numbers of measurements at staggered sub-frame intervals.

The fact that these intervals are only a fraction of a frame long increases SPI’s frame rate. However, the measurements in each self-contained frame become successfully higher frequency—recording more fleeting (rather than general) aspects of a scene. This progression ensures that quick movements are recorded properly. Instead, sliding windows contain lower- and higher-frequency measurements that are out of kilter with one another, reintroducing blur or even creating ghost images.

Yu and colleagues' solution is to combine sliding-window SPI with a novel estimation of “optical flow.” The latter involves working out on average how much motion there should be between successive pixel measurements, something already done quite accurately using deep learning. The new work involves reconstructing low-resolution images of a scene using just the low-frequency measurements from two successive frames, then comparing those two images and interpolating between them so that the low-frequency and intervening high-frequency measurements can be made consistent with one another.

After carrying out simulations involving publicly available videos depicting buses and other fairly fast-moving objects, the researchers put their scheme to the experimental test. They did so by modulating light after it reflected off an object, which entailed shining white light at the object placed onto a moveable vertical surface, then focusing the reflected light on to a digital micromirror device. They directed the modulated light at a very sensitive single-point detector, which converted the received intensity into a voltage signal.

The researchers imaged a series of objects, including a picture of a car and a plastic doll, which they moved in straight lines and also rotated. They found they could improve both the quality and temporal resolution of these images compared with those of other, often simpler objects used in tests of other SPI imaging methods.

Striking a balance

They add, however, that their approach suffers from a couple of shortcomings. One is the significant amount of processing needed to work out the optical flow. They estimate that this might reduce the frame rate to around 8 frames per second for a 1024×1024–pixel scene and a 25% sampling rate—just one tenth that of unadorned sliding-window SPI. But they say that this bottleneck does not affect the acquisition of raw measurements (as opposed to displaying the results), arguing that the delay needed for processing would still be acceptable for many applications, such as remote sensing.

Added to this, however, is the problem of assuming uniform motion when calculating optical flow. As the researchers point out, that assumption doesn’t hold for more complex motion such as acceleration or deforming soft objects. A higher frame rate would help mitigate this problem, they say, but that in turn would reduce image quality, which would itself compromise the optical flow calculation. “This creates a performance-limiting feedback loop that must be carefully balanced,” the team said.