Tess Eidem holds up a jar of fungus used to generate allergens for research. [Image: Patrick Campbell/CU Boulder]

Nearly one-third of US adults and children have been diagnosed with an allergic condition, with reactions that can range from mild to severe. Airborne allergens are often proteins derived from animals and plants that can remain structurally stable in indoor environments for years.

Now, researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder, USA, have developed a device that leverages ultraviolet (UV) light to disable airborne allergens (ACS ES&T Air, doi: 10.1021/acsestair.5c00080). Exposure to far-UVC light centered at 222 nm—a wavelength known for its high ability to kill pathogens—significantly reduced allergen levels compared with control conditions.

“Far-UVC could be installed in homes, schools, hospitals or workplaces as a passive, fast-acting way to improve indoor air quality, and it may complement other allergen-mitigation strategies like cleaning and air filtration,” said study author Tess Eidem. “This technology has the potential to be another layer of protection for people with severe allergies or asthma.”

Reduction in allergens

Conventional UV treatment of indoor air and surfaces uses bandwidths centered around 254 nm, which can cause DNA and skin damage. Eidem and her colleagues wanted to see if far-UVC light, considered safer than traditional germicidal UV light, could provide a practical way to inactivate these allergens directly in the air we breathe.

“Allergies and asthma affect millions of people worldwide, and airborne allergens from cats, dogs, dust mites, mold and pollen can be concentrated indoors and contribute to or exacerbate these symptoms,” she said. “Airborne allergens are especially challenging to control indoors, so my work focuses on exploring ways to remove or inactivate them in the air.”

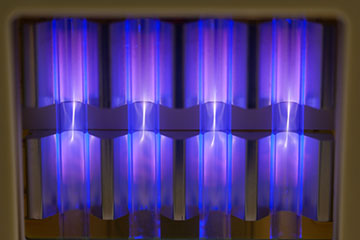

The researchers first developed a controlled experimental system to generate breathable particles containing common allergens from mites, pet dander, mold and pollen. The particles were released into the air of an aerosol chamber the size of a small room. They then switched on four lunchbox-sized far-UVC lamps on the ceiling and floor for 30 minutes, sampling the air every 10 minutes.

UV222 lights hang on the ceiling of the Aerobiology and Disinfection Laboratory at the University of Colorado Boulder. [Image: Patrick Campbell/CU Boulder]

The allergen levels were quantified afterward using an antibody-based immunoassay, which relies on intact protein conformation for antibody–allergen recognition, binding and quantification. Compared with identical control conditions, exposure to far-UVC light effectively decreased airborne allergen levels by about 20% to 25% on average.

A safer wavelength

Eidem and her colleagues hypothesize that airborne protein allergens exposed to far-UVC light at 222 nm undergo structural changes that reduce antibody–allergen epitope binding.

“This wavelength of UV light interacts with proteins, including protein allergens, and we believe that it may change their structure to ‘inactivate’ them,” said Eidem. “Importantly, this wavelength of UV light is considered more ‘occupant safe’ than conventional germicidal UV light at 254 nm and doesn’t penetrate as deeply into human skin or eyes.”

Future work will investigate the mechanism of how far-UVC light may reduce immunodetection of these airborne allergens. The researchers also want to explore how airborne allergen reductions translate into actual symptom relief for people with allergies or asthma.