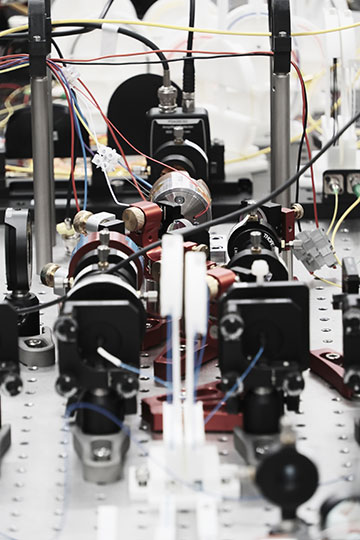

Researchers have used optical parametric oscillators to provide the entanglement needed in a demonstration of the virtues of quantum learning. [Image: Jonas Schou Neergaard-Nielsen]

Scientists say they have for the first time used a photonic quantum system to learn tasks that would be practically impossible to do on a classical machine (Science, doi: 10.1126/science.adv2560). Although the tasks in question are very specialized, the researchers argue that their system could be scaled up to yield new kinds of sensors and other devices.

The quantum advantage

The ability of quantum states to exist in superpositions and become entangled has for many years offered the enticing prospect of computers that exploit massive parallel processing to vastly outstrip their classical counterparts. That prospect was boosted in 2019, when researchers at Google, USA, announced they had used a computer comprising a mere 53 superconducting quantum bits to execute a specific, niche program—one generating a semirandom series of numbers—in around three minutes, compared with the 10,000 years that they claimed would be needed by a state-of-the-art classical supercomputer.

That assertion of so-called quantum supremacy, since rebranded as quantum advantage, was disputed by other physicists, who argued that the Google team had underestimated the capabilities of existing classical machines. But some of the Google researchers have since gone on to demonstrate the advantage bestowed by what is known as quantum learning, which involves collecting multiple data samples to find out a specific property of a quantum system such as a device’s noise characteristics. In 2022, they reported having used a 40-qubit superconducting computer to slash the number of samples needed for such learning by about a factor of 100,000, compared with classical methods.

All quantum computing technologies have their pros and cons, however. Although they are relatively easy to scale up (being solid-state devices), superconducting processors have fairly short coherence times and must be chilled to low temperatures.

Exploiting squeezed light

Ulrik Andersen at the Technical University of Denmark and colleagues in Denmark, the United States, Canada and the Republic of Korea reckon that quantum learning is better carried out by probing systems that use quantum states of light rather than matter. In the latest work, they show how to achieve a huge advantage over classical systems by exploiting what is known as squeezed light—light whose phase noise has been beaten down to beneath the usual quantum limit at the expense of amplitude noise or vice versa.

With each probe of the channel consisting of multiple modes, the idea was to establish how many probes were needed to faithfully recreate the main features of the Fourier function for a given number of modes.

The researchers used a pair of optical parametric oscillators to entangle two streams of photons, one a “probe” and the other “memory,” with a given amount of squeezing. They simulated the effect of passing the probe through a certain noisy channel by mixing those photons with others having a modulated coherent state, and then they carried out a Bell measurement between the modified probe and memory states, thereby sampling the channel’s modulation characteristics.

To demonstrate that this setup could characterize the channel better than a purely classical scheme, Andersen and colleagues calculated the Fourier transform of the modulation’s probability distribution over multiple measurements. With each probe of the channel consisting of multiple modes, the idea was to establish how many probes were needed to faithfully recreate the main features of the Fourier function for a given number of modes.

They found that the answer depended heavily on the degree of squeezing, showing that even with relatively few modes they could speed up the measurement process by several orders of magnitude. For 30 modes, they found that a little under 5 dB of squeezing yielded the same accuracy with 1,000 samples as a classical probe did after about 10 million. For 100 modes, the speed up when extrapolated would be even more dramatic—lowering the sampling time by nearly 12 orders of magnitude. They say that when sampling at 1 MHz with some redundancy to build up statistics, a measurement normally lasting 20 million years would instead take just 15 minutes.

Demonstrating advantage and beyond

The researchers add that this demonstration does not, strictly speaking, prove definitive advantage over classical sampling, since their experiment only analyzed a specific family of noisy channels. But they also carried out a variation on the experiment that essentially distinguished the noise characteristics from two possible families, observing a significant 109-fold reduction in sampling time—and in this case, they say, demonstrating definitive advantage.

Collaboration member Jonas Schou Neergaard Nielsen, also at the Technical University of Denmark, acknowledges that, like the earlier Google demonstrations of quantum advantage, the latest research does not involve a useful task. But he believes that the work can have real applications, such as error mitigation in quantum communication and in shaping future photonic quantum processors. He also hopes that the new results will “open other researchers’ eyes to the potential of massive quantum advantage” in areas beyond quantum computing.