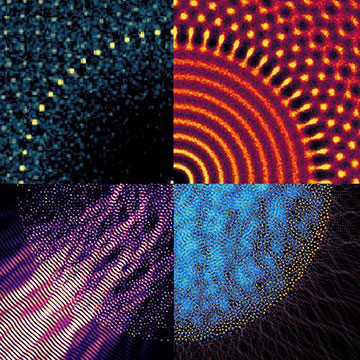

Researchers at New York University have simulated a material they call a gyromorph. A 60-fold version of this material would have the structure factor and pair correlation function seen (top left and right), while the system would reflect a polarized light beam and deplete energy states (bottom left and right). [Image: The Martiniani lab at NYU]

Scientists in the United States have developed a new kind of disordered material that they reckon might in future guide light around the insides of optical computers (Phys. Rev. Lett., doi: 10.1103/gqrx-7mn2). They have yet to make the “gyromorph” material in the lab but have shown through simulations that it should block the passage of certain frequencies in all directions.

Blocking light in 3D

For decades, researchers have been guiding light using photonic crystals. These materials consist of structures varying periodically in refractive index, and they impede transmission of specific bands of electromagnetic radiation just as the variation of potential within semiconductors blocks certain bands of electronic energy. However, given the symmetries inherent to their periodic structure, photonic crystals do not block light in all directions—instead exhibiting an anisotropic band gap.

More recently, some groups have shown how to block light isotropically using aperiodic materials. Initially limited to two dimensions, last year Paul Steinhardt at Princeton University and colleagues blocked light in three dimensions (at microwave frequencies) using a so-called disordered stealthy hyperuniform structure.

However, as Stefano Martiniani and coworkers at New York University explain in the latest research, even though these structures displayed isotropic band gaps, their blocking effect was limited, which reduced light transmission in all directions but only partially.

A novel material

To try and achieve more pronounced three-dimensional isotropy, Martiniani and colleagues asked themselves whether there is a feature common to all materials displaying isotropic photonic band gaps. To do so, they considered the single-scattering regime, an idealized scenario in which incoming photons only scatter once when entering a material. They say that under these conditions, a band gap arises due to strong scattering at one particular frequency and weaker scattering at neighboring frequencies.

They found that the novel materials should block light more completely in both two and three dimensions.

Looking at all the aperiodic systems with isotropic photonic band gaps that have been studied to date, the scientists realized that the systems all have “an isotropic ring of high values” in the scattering parameter known as the structure factor. They then sought to accentuate this property as far as possible and ended up with correlated disordered structures that they call “gyromorphs”—materials having a liquid-like absence of translational structure but rotational order at large scales.

The researchers simulated gyromorphs using spectral optimization methods and then compared the results with the properties of hyperuniform structures, quasicrystals and other competing systems. They found that the novel materials should block light more completely in both two and three dimensions.

Future testing and applications

To turn gyromorphs into experimentally testable structures, Martiniani’s colleague Mathias Casiulis says that experimental collaborators in Switzerland are looking to fabricate them using 3D printing. Casiulis reckons this ought to be fairly straightforward to do at microwave or infrared wavelengths, but he adds that there will be “a few more experimental hurdles” when fabricating the materials in the visible range, explaining that smaller-scale structures are more expensive to produce and harder to make accurately.

Once realized, the researchers believe that these materials could be used to make a variety of optoelectronic components, such as free-form waveguides and coatings with tuneable reflectance. Their unique properties, they argue, might even be exploited to make optical computers—futuristic devices that in theory could operate far more quickly and efficiently than existing computers but require waveguides that can steer light around photonic chips with minimal loss.

Casiulis says that other groups have already fabricated prototype waveguides but explains that those devices are expensive and ill-suited to fully fledged optical computers. “That is why a lot of the effort has to do with materials science,” he says. “One needs to make the performance, flexibility and manufacturing cost of components compatible with large-scale fabrication.”