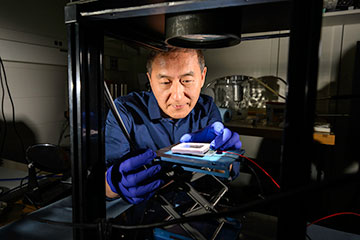

Chunlei Guo tests his group’s solar thermoelectric generator. [Image: University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster]

Scientists in the United States have used femtosecond lasers to boost the power output of a solar thermoelectric generator by etching nanostructures to improve the device’s heat-transfer properties (Light Sci. Appl., doi: 10.1038/s41377-025-01916-9). The generator is also compact and contains no moving parts, so they reckon that it could one day be used in wireless sensor networks or wearable electronics, among other applications.

Suffering from low efficiencies

Solar thermoelectric generators (STEGs) exploit the fact that charge carriers diffuse from hot to cold regions within a material, thereby producing a voltage. Unlike photovoltaic cells, whose narrow bandgaps limit the range of frequencies that generate carriers, thermoelectric devices can in principle extract energy from across the solar spectrum. To date, however, they have suffered from low efficiencies—typically converting less than 1% of sunlight into electricity, compared with around 20% for commercial solar panels.

Researchers have tried for decades to increase the efficiency of the semiconductor materials used in STEGs but had limited success. Chunlei Guo and colleagues at the University of Rochester have instead sought to raise the temperature difference between the two ends of a generator, since the device’s power output is proportional to the square of both the material efficiency and temperature difference.

Back in 2011, Guo’s group showed how to make the hot end of a STEG significantly hotter by using a femtosecond laser beam to etch nanostructures in a piece of aluminum foil. By creating a series of precisely shaped grooves on the metal surface, which enhances the surface’s absorption of solar radiation at visible and ultraviolet wavelengths while minimizing emissions in the infrared, they were able to maximize the foil’s solar-thermal heat generation. When integrating the foil into the STEG’s hot end, the scientists found they could boost the generator’s efficiency by up to a factor of nine compared with a device without the foil.

Maximized heat generation

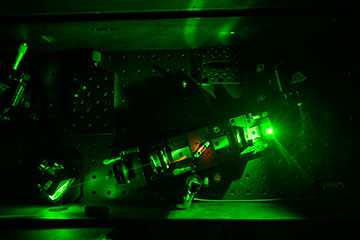

In the latest work, Guo, Subhash Singh and colleagues at Rochester have sought to further exploit the qualities of femtosecond-laser processing—a single-step, scalable technique that they say is simpler and more versatile than multistep coating technologies. This time, they used a femtosecond laser to maximize the heat generation of tungsten, which absorbs (and therefore emits) far less radiation in the infrared than does aluminum. But they also put the laser to use for the cold end, exploiting aluminum’s high infrared emissions to maximize heat dissipation, further increasing a STEG's temperature difference.

Researchers used a laser to generate ultrafast laser pulses that etch nanostructures onto metal surfaces, creating highly efficient STEGs. [Image: University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster]

What’s more, they added a “greenhouse” to the tungsten to minimize convective as well as radiative losses at the hot end. This involved surrounding a STEG with foam walls that extended beyond its hot (sun-facing) end and then stretching a food-wrap film across the top of the walls, limiting the replacement of air heated by the hot surface with cooler surrounding air.

The researchers optimized their design by simulating each part separately. This involved tuning the size of the tungsten nanostructures by playing with the laser processing parameters, trading off the width and depth of the aluminum’s micrometer-sized grooves, and finding the optimal depth of the greenhouse chamber to minimize both convection and conduction (the former process benefiting from a bigger space while the latter is impaired).

Putting all the pieces together in a device measuring 20 × 20 × 6 mm, the researchers found they could boost the STEG’s power output by around a factor of 15 compared with a device equipped only with a standard aluminum heat dissipator (although the benefit lessened slightly at higher solar concentrations). To demonstrate the practical benefit of such increased output, they showed that a simple STEG cannot power a light-emitting diode even under 10×-concentrated sunlight, whereas the fully enhanced STEG can perform the task with 5× concentration.

Limited but useful

Despite the improvements, the Rochester device remains limited by the intrinsic properties of the semiconductor material at its core, still having an efficiency of less than 1%.In comparison, a Stirling engine, which converts thermal energy to electricity in two steps (using the cyclic expansion and contraction of a gas to generate motion that turns a generator), typically has efficiencies of 10 to 25%. Closing this gap, says Singh, will mean improving the performance of the semiconductor material by around a factor of 50.

However, the researchers point out that unlike Stirling engines, their STEG has no moving parts and therefore requires little maintenance. It is also quite compact compared with other STEGs, some of which use bulky vacuum equipment to limit convection at the hot end, while boosting convection at the cold end with large metallic fins. The combined additions at the two ends of their device, they say, added just 25% to the weight of a standard STEG.

Such virtues, the team maintains, could eventually see STEGs employed in a variety of applications that call for a continuous, reliable, battery-free source of power, such as wireless sensors for the Internet of Things, wearable devices and off-grid renewable energy systems in rural areas.