Shirley Malcom.

The 25 May murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white Minneapolis, USA, police officer—captured on video and shared and seen worldwide—triggered international outrage and a wave of protests and demonstrations. In the wake of those protests, there have been calls for the scientific and academic communities to own up to systemic racism in their institutions.

Earlier this month, OPN spoke with Shirley Malcom, who has advocated for decades for better representation of underrepresented groups in science and engineering, about the current state of Black representation in physics. For many years the head of education and human resources programs at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Malcom is now the senior advisor and director of STEMM Equity Achievement (SEA) Change, an initiative to improve diversity and inclusion in higher education through a proven self-assessment process for academic institutions.

Recently, Malcom wrote the foreword to the 2020 TEAM-UP report, which summarizes the findings of the American Institute of Physics’ (AIP’s) National Task Force to Elevate African-American Representation in Undergraduate Physics and Astronomy. We talked with her about those findings, and also about the current effort at SEA Change.

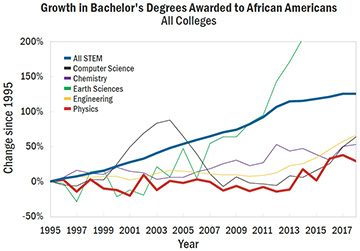

In your foreword for the TEAM-UP report, you noted that although the percentage of bachelor’s degrees awarded to African Americans in other areas of science has been trending up, the needle has barely moved for physics. Why do you think that physics has been so resistant to Black representation?

While the number and percent of Black undergraduate degrees in various scientific disciplines has grown in the last 20 years, representation in physics remains stagnant. [Source: NCES Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) / AIP TEAM-UP report] [Enlarge image]

Physics is its own kind of world, and I don’t think that we really appreciated the extent to which the historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were actually contributing to the physics numbers—even though very few of the institutions actually have full-blown physics majors.

So the question is, where do people go? Given that there are all these physics departments that are out there [at predominantly white institutions (PWIs)], what are they producing? If they aren’t having African-American students coming in as majors, have they ever questioned why?

While George Floyd was the precipitating thing, it wasn’t the first time and it won’t be the last time. It is a systems problem—in the same way that trying to do something about diversity within physics is a systems problem. It’s a system of problems that the physics community has to own.

Given the current climate in the U.S., now seems like an appropriate time for introspection. What are some of the questions that physics departments should be asking themselves?

There’s a lot of exploration that individual departments need to do. There are some things that they need to understand. A lot of the high schools, for example, that are educating African-American students don’t necessarily have strong physics course availability, like advanced placement (AP) Physics.

“Trying to do something about diversity within physics is a systems problem. It’s a system of problems that the physics community has to own.”

—Shirley Malcom

I chair the Board of the National Math Science Initiative (NMSI), which advances the idea of “AP for all” in its College Readiness Program. Because, in the past, AP hasn’t been available everywhere and oftentimes has been a referral thing. I think that an interesting question to ask is whether or not students have early access to the coursework that would allow them to pursue physics in college.

The next question is, do they have to have taken AP Physics to pursue physics once they get to college? When a faculty looks out into the intro courses they teach, who do they see? And who do they see as potential majors? Do they see teaching that intro course as being a duty, or as an opportunity to seduce and entice students to the study of the field?

And it isn’t just a matter of attracting—to what extent are you retaining minority students? With something like photonics, for example, I don’t think enough students really understand its practical applications—that’s a major issue. Where are the opportunities to engage students with the kinds of experiences that do hold them to the field? Where is the chance to even see somebody who looks like them who does this work?

Within SEA Change, we’re doing a webinar series called “Talking about Leaving Revisited,” which is based on the book that unearthed this whole issue of the quality of teaching, especially what happens to different students based on that teaching quality. What do we see as retention strategies?

SEA Change took some inspiration from the gender equity program Athena SWAN, as I understand it. But it seems to have a broader aim.

We are absolutely focused on gender equality, but we can’t stop there. In our case, we have to look at race, ethnicity and we really have to look at women of color. Things are particularly bad for women of color, and it’s going to be hard to push up the overall women’s numbers when the women of color are so far down. If you don’t separate that out, you’re not going to really understand where your challenges are. That is one of the reasons that we’ve expanded on the Athena SWAN model.

“Things are particularly bad for women of color, and it’s going to be hard to push up the overall women’s numbers when the women of color are so far down.”

—Shirley Malcom

I was reading an article about a conference that focused on women of color, and the kinds of comments that come from the women about their experiences in their physics program—like they were dissuaded from applying, or they were told outright that maybe they should think about changing their major.

If somebody looks at us, we don’t look like what they are used to seeing. And that’s not on us; that’s on them—that’s their problem. But it becomes ours when they use it as a criterion for determining opportunity.

What are some other ways in which systems can re-evaluate opportunity?

In so many of the cases, students who have come from weak K-12 programs—they’re not dumb, they’re underprepared. And even providing opportunities for support programs within the institution can get them over that hump. For these young people, there ought to be somebody out there who could help give them a hand—not a handout, a hand—to get them to a place where they can make it themselves.

A lot of the students also have financial problems. They are working multiple jobs and they cannot study if they are trying to put in 20 to 40 hours to pay for their education. And they are in competition with students who are only being asked to study. Tell me, at the end of the day, who would you bet on? All of this is really starting to raise serious questions about opportunity.

Can you talk a bit more about retention?

Where I have a problem is, I cannot figure out how to change people’s minds about who could be successful. These students are not able to find community. If they’re not able to feel welcomed, if they’re not being valued, if there is not attention to the microaggressions that they may experience because they are different from the people who are around them—those kinds of things could push students out, not just being capable or not being capable.

I think, to a certain extent, that is what students find in HBCUs—somebody who is not going to just cast them aside to “thin the herd.” How you teach somebody really matters. You can either position them for success, or set them up for failure.

We’re losing talent. Not because they are wandering off, but because we’re pushing them out—especially women of color.

“We’re losing talent. Not because they are wandering off, but because we’re pushing them out.”

—Shirley Malcom

Given the lack of progress, it must be difficult to maintain a sense of optimism that things can change. Recently, have you found reason for optimism?

I have found new optimism through SEA Change. Fifteen years of history for Athena SWAN has shown us that it is possible to move this stuff if you take a very structured, systems approach and get institutions to be really honest about themselves and about what is going on inside.

This may surprise you, but it is also the very disruption that we are experiencing right now [with the pandemic] that is giving me the greatest hope. Our institutions are not going to be the same when we return to them. Whatever we return to, there’s an opportunity to reimagine them, reinvent them in ways that support diversity, equity and inclusion.

“Old” is not an option. If you’re going to reinvent, you might as well go all the way. That’s the mantra that I am putting out there.

To learn about some of OSA’s activities and resources to dismantle systematic racism, visit www.osa.org/CommitToChange.