![]()

[Image: POM/USC]

As evidence of climate change has mounted, many scientists have become preoccupied with the impact of travel, including to scientific meetings, on the global carbon budget—and are seeking alternative, more sustainable approaches for sharing ideas. One community of photonics researchers has pulled together a prime example, the Photonics Online Meetup (POM), which kicks off with a virtual poster session today and culminates in an online conference on Monday, 13 January, complete with scientific talks and discussion.

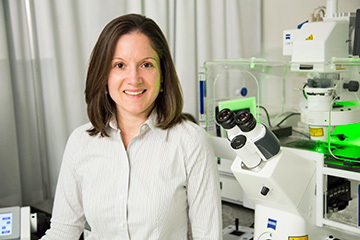

On the eve of the conference, OPN talked with one of its co-chairs, OSA Fellow Andrea Armani of the University of Southern California (USC), about the roots of POM and where it’s going.

Overcoming limitations

Armani says that the seeds for POM were planted, as many other ideas are, in the “free-form chaos” of Twitter, and in discussions there with colleagues about some of the limitations of conventional conferences. And, while environmental sustainability was an important motivator for thinking about a new approach (and constitutes a key theme in POM’s mission statement), it wasn’t the only one.

“As research is becoming more interdisciplinary,” Armani explains, “everything surrounding conferences” has become more complex and burdensome. In her role as a physicist who works on new materials for photonic devices, she notes, she finds herself required to attend meetings not only in photonics but in materials science, chemistry, and other areas. “It’s exhausting,” says Armani—adding that the cost and time commitments, as well as visa restrictions, often make it particularly difficult for junior faculty and students to attend conferences. “Everything just kind of compounds,” according to Armani.

With these sustainability, cost and time issues in mind, when the idea came up in discussion on Twitter to hold a free online photonics conference, “everyone said, Yeah, that’s a great idea; we should do that,” Armani recalls. “And it snowballed from there.”

Pent-up demand

Andrea Armani. [Image: Courtesy of A. Armani/USC]

Once the idea had been hatched, in many ways the planning for POM took a path familiar in other conferences, with Armani and her fellow co-chair, OSA member Orad Reshef of the University of Ottawa, Canada, overseeing the planning and putting together an organizing committee of five senior scientists. The co-chairs and organizing committee settled, through a vote, on three topic areas for the first POM—integrated optics, nanoscale quantum optics, and optical materials. Then, they recruited invited speakers for each topic, and started putting out the call for abstracts.

Armani says that the call resulted in “about 103 or 104 abstracts submitted to the three topic areas … I was pretty excited by that, because we had only nine slots.” Also exciting to Armani has been the number of registrants to the conference. “When we started this, our goal was, OK, we’re hoping to get 30 people to attend our online event—we’re going to call that a success,” she says. As of the morning of 7 January, she reports, “we have 670 people registered” (more than 50% of them students), along with 60 “POM hubs” scattered worldwide, where multiple participants will come together in single locations to experience Monday’s online conference together.

“Clearly,” Armani says, “we aren’t the only people looking for different ways of sharing information and sharing research results.”

Twitter threads and streaming

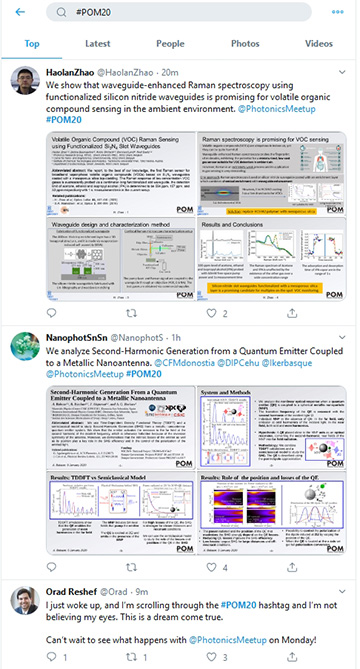

The POM conference begins with a virtual poster session on Twitter, in which authors of accepted posters make them the anchor of Twitter threads (with the hashtag #POM20) for discussion of the work.

The sharing has, indeed, already started, with the conference’s virtual poster session, which is spooling out on Twitter as this story is being written. In this part of the event, researchers whose posters have been accepted for the conference will post them to their Twitter accounts, using the hashtag #POM20, and will create brief, explanatory Twitter threads attached to the posts. Those threads will then host, online, the kind of discussion that, in a live meeting, would take place in front of a poster tacked up on a bulletin board.

The official “live” POM conference will take place on Monday, 13 January, from 2:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. Eastern U.S. time. (Registration for the conference is free and was still open as this story was being written.) The conference will be 100% virtual, with invited speakers and others participating remotely via web conferencing software. And the conference participants, both speakers and audience, will be distributed worldwide—“they’re kind of scattered everywhere,” according to Armani.

The specific, many-to-many nature of the conference required Armani and Reshef to come to grips with a variety of technical requirements, including finding software (Cisco Events) that could handle online streaming with multiple inputs and multiple outputs simultaneously, and arranging for the I.T. infrastructure (hosted at USC). It has also put them to work with the minutiae of doing video and sound checks with presenters—and creating contingency plans in the event of technical problems.

Electronic coffee break

Beyond technical issues lies the larger question of how such a virtual conference will work as a networking forum. It’s well known that many interesting interactions at conferences take place during coffee breaks, informal gatherings, hallway conversations and other venues beyond scientific talks.

Armani acknowledges that the same vibe may be difficult to re-create on the day of the online conference. But she hopes that the virtual poster session on Twitter—which, unlike poster sessions at a live, in-person meeting, can continue indefinitely—will engender similar conversations and ongoing interactions online. “A student posting a poster of their research,” says Armani, “will give another researcher a reason to contact them and actually start a discussion.”

Another vehicle for networking are the POM hubs—local viewing sites at which attendees, particularly students, can “get together and watch the talks as a group, as opposed to sitting alone in an office somewhere,” Armani observes. These could serve, in her view, as a catalyst for making introductions, especially among students, in a particular locality or city, and building peer networks there. (Many of the POM hubs worldwide are being organized and hosted by OSA student chapters, and The Optical Society will also host a hub at its headquarters in Washington, D.C.)

Gauging outcomes

How will success be measured for POM? In one respect, Armani notes, the project has already exceeded its initial, modest goal of 30 online attendees, with registration more than 20 times higher than that. But the team is also looking at more rigorous approaches to gauging the conference outcomes. For example, the POM group is partnering with Gisele Ragusa, a professor of STEM education and engineering at USC, to develop a learning-effectiveness survey that will be given to all of the attendees, to assess POM’s utility.

The team will also be assessing quantitative statistics on usage, engagement and activity from the software itself—both during the live event, and in the several weeks afterward, during which the talks will be posted online. The latter will be of particular interest, in Armani’s view, because the worldwide nature of the conference makes it impossible to choose a time that works for everyone. “This will give us insight into the countries, especially in Asia, where the time zones are just incorrectly synched.”

Beyond the “first two rows”

The lessons learned from the initial conference will feed into future, similar efforts, not only in photonics but in other areas. “We definitely see this kind of online conference, or online meetup platform, translating to multiple other fields,” says Armani, who adds that the POM group has “received a lot of inquiries” from other researchers not only in fundamental physics but in areas such as biology and education. “They’re watching to see how our event unfolds,” she says, “and to learn from our successes and failures.”

Meanwhile, Armani and her colleagues are focusing on, and looking forward to, Monday’s online conference—and particularly on how the online format might shape the group dynamics of the conference sessions.

“My experience as a session chair [at in-person conferences] is that all of the questions come from the faculty members in the first two rows,” Armani says. “But here, there won’t be a first two rows. So I’m really curious what types of questions we’re going to get, because we’re removing that barrier. I’m excited to see what happens.”