Clara Saraceno (left) and Anna Ono Suzuki in the lab. [©RUB, Marquard]

Clara Saraceno (left) and Anna Ono Suzuki in the lab. [©RUB, Marquard]

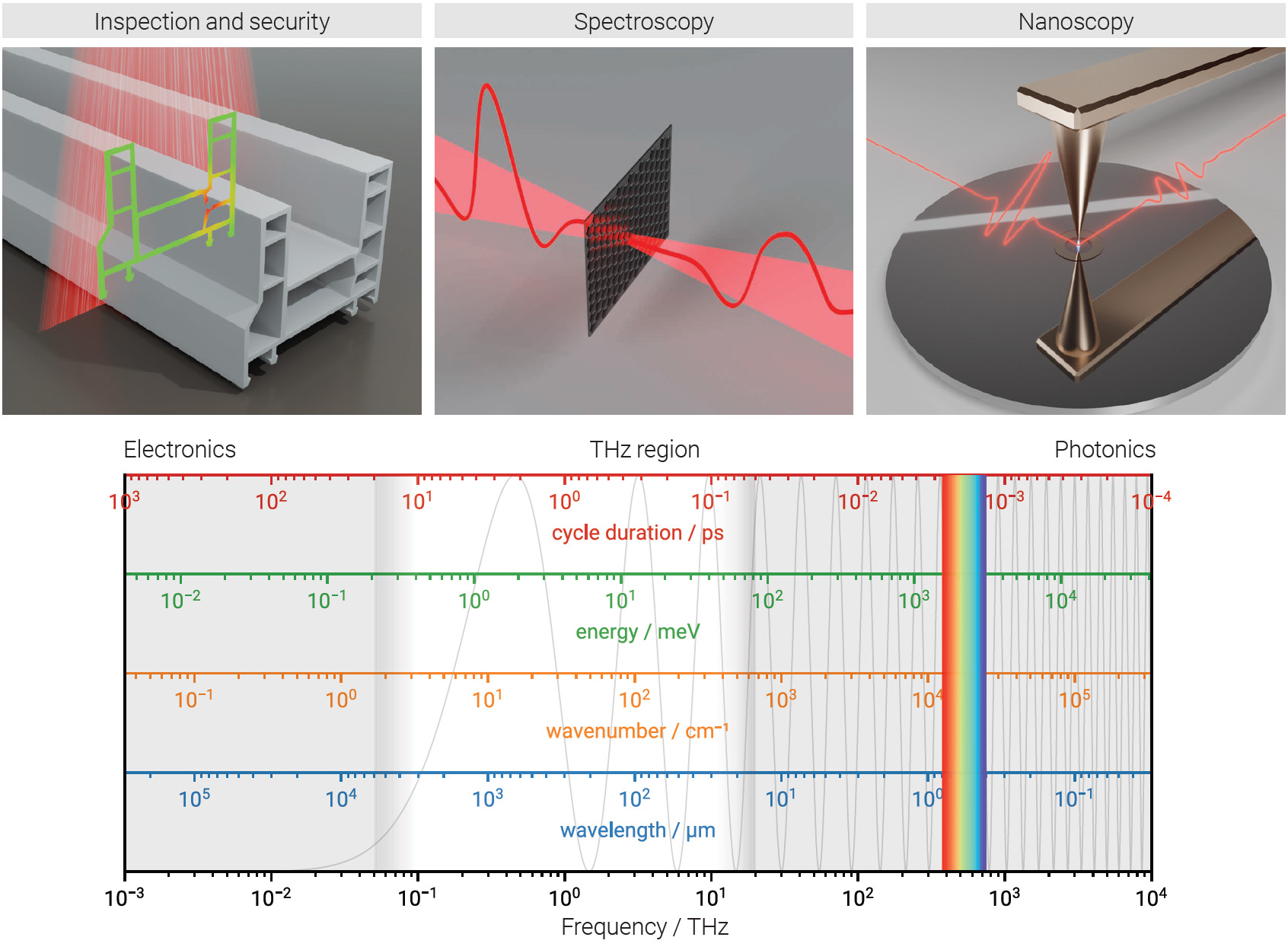

Electromagnetic radiation in the terahertz (THz) frequency region is gaining popularity across an increasingly wide range of scientific and technology fields. This spectral region, loosely defined as spanning 100 GHz to 30 THz, was traditionally referred to as the “THz gap” due to the lack of technologies that could efficiently generate and detect such radiation, which lies between millimeter-wave electronics and photonics. Today, however, this term has become outdated, and the generation, manipulation, detection and application of THz radiation are now highly active areas of research, with technologies increasingly reaching commercial systems and industrial applications.

THz radiation has moderate photon energies (in the meV range) and produces more divergent beams than optical and mid-infrared light (due to their longer wavelengths), rendering it safe in most application scenarios involving human operation. Its frequencies allow us to inspect objects and see through materials opaque to higher frequency light, while simultaneously providing greater spatial resolution than longer millimeter waves. THz waves also offer ultra-broad bandwidths for communication and can excite and probe a plethora of fundamental low-energy phenomena in solids and liquids on (very fast) picosecond timescales.

Ultrafast advances

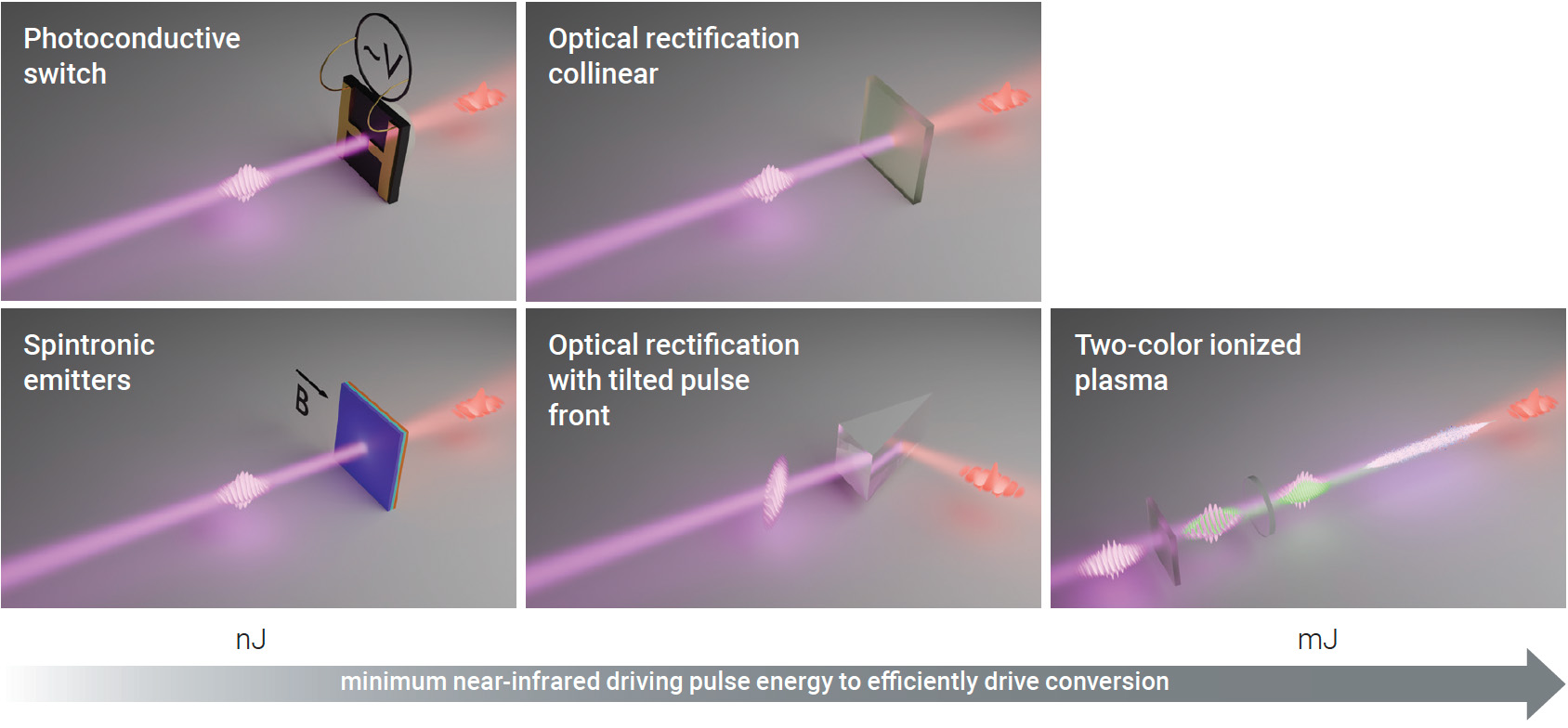

Among the various technological approaches advancing this frequency region, ultra-broadband THz sources that generate very short pulses have shown especially rapid progress in recent years. In particular, table-top systems driven by ultrashort-pulsed lasers in the near-infrared, which convert that radiation into longer wavelengths, have made tremendous leaps forward. The most commonly used techniques for generating ultra-broadband THz pulses using ultrafast lasers include frequency down-conversion in materials with second-order (χ(2)) nonlinearity using intra-pulse difference frequency generation (often referred to as optical rectification); photocurrents in biased semiconductors; and photocurrents in ionized plasma.

Each of these techniques offers distinct advantages and limitations, providing access to different parameters in terms of bandwidth, pulse duration, peak electric field strength, beam quality and polarization states. The choice of method depends on the desired parameters for a given application. Most modern methods reach short single-cycle transients of hundreds of femtoseconds to a picosecond duration. Adhering to the classical time–bandwidth correlation, these sources provide ultra-broad bandwidths that can span several tens of terahertz, as well as strong peak electric fields exceeding MV/cm. Most critically, the performance of these sources is limited by the available driving lasers. In this context, progress in laser technology has therefore always been—and continues to be—essential for advances in ultrafast THz technology and its applications.

Continuous improvements in broadband THz sources have significantly impacted a wide range of scientific disciplines, including physics, chemistry, materials science, engineering, biology and medicine. They allow researchers to probe and manipulate low-energy phenomena and study time-resolved dynamics related to charge carriers, phonons, spins, conductivity and intermolecular bonds in liquids, among others.

Advances have even allowed sub-wavelength resolution using near-field techniques, reaching down to the angstrom level in recent studies. These short-pulse THz sources also play a critical role in industrial processes, including material identification and imaging. For instance, they are used in quality control of layered materials via time-of-flight sensing techniques and in the inspection of historically relevant artwork and other objects. Furthermore, they are ideally suited for hyperspectral imaging inside optically opaque materials, such as for the identification of counterfeit pharmaceuticals in plastic packaging.

Despite this promise, many applications are still severely limited by the persistent lack of higher average powers, with typical values ranging from tens to hundreds of μW. This limitation directly impacts measurement speed and signal-to-noise ratio, preventing the widespread deployment of THz technology in scenarios demanding rapid sample evaluation or complex multidimensional spectroscopic scans.

[Enlarge image]Some examples of modern applications of THz frequencies and the THz region in the electromagnetic spectrum. [M. Saraceno]

[Enlarge image]Some examples of modern applications of THz frequencies and the THz region in the electromagnetic spectrum. [M. Saraceno]

Why is high average power critical?

THz frequencies are strongly absorbed by atmospheric water vapor, particularly at high frequencies (above 1 THz), which are commonly generated using ultrashort pulses as drivers. Compared with millimeter waves, THz radiation suffers from more pronounced scattering losses, though beam divergence remains relatively moderate. All of these factors mean that detector-ready signals in real scenarios are often very weak.

In scientific applications seeking to study ultrafast dynamics, low average power translates into long acquisition times, severely limiting experiments that require multidimensional time and frequency scans or measurements that are not repeatable and thus cannot be captured with pump–probe type schemes. In industry, the slow acquisition speed of these sources prevents deployment of THz imaging and inspection in fast-moving production lines.

Boosting the average power of THz sources is one of the key challenges or “holy grails” on the roadmap for THz science and technology.

For these reasons, boosting the average power of THz sources is one of the key challenges or “holy grails” for the progress of THz science and technology. To grasp the relevance of increasing the average power of laser-driven short-pulse THz sources, it is essential to understand not only the difficulties of propagating THz light with low loss, but also its impact on the detection schemes used to measure them and the fundamental relationship between signal quality and measurement speed.

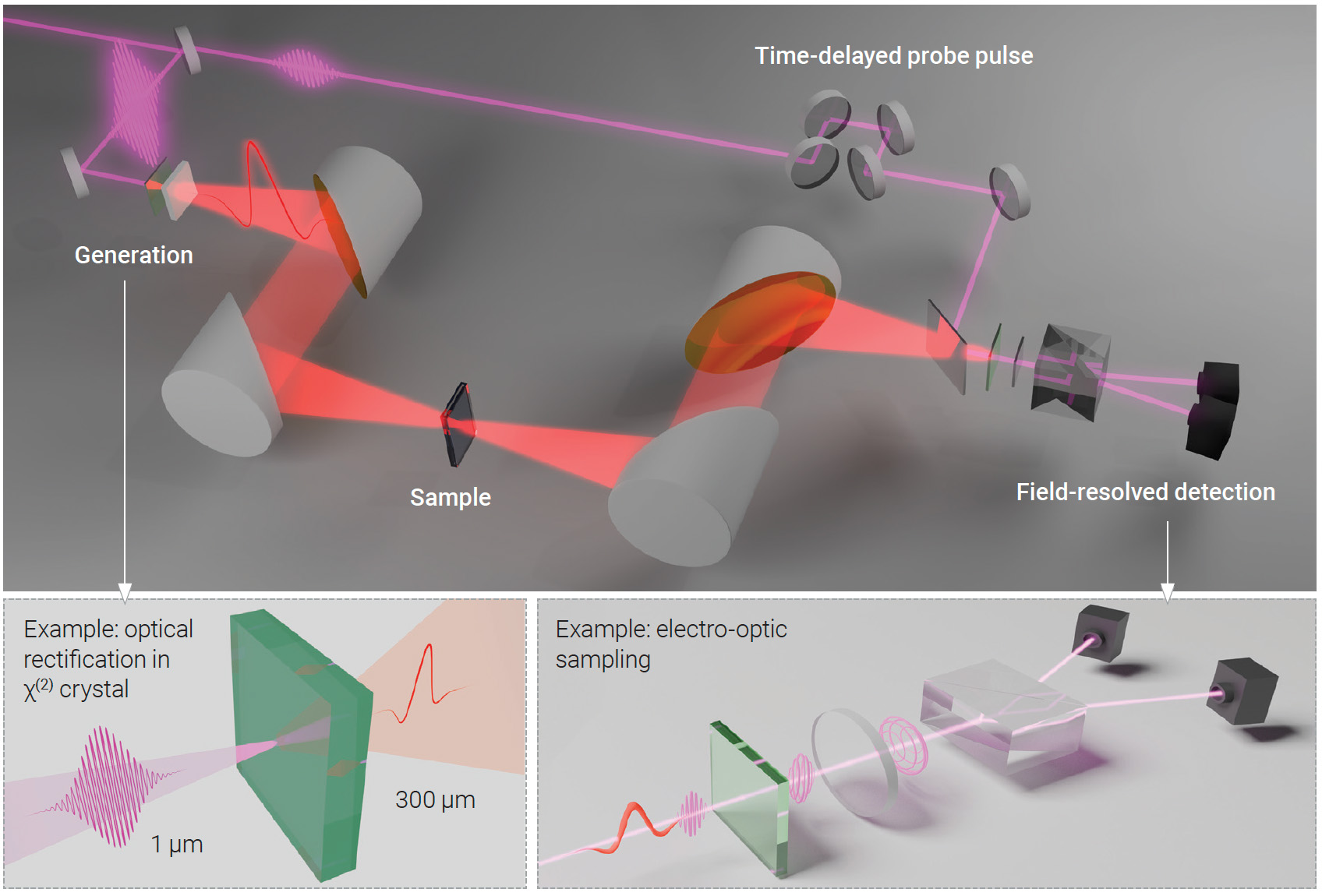

A typical THz pulse generated by an ultrafast laser exhibits single-cycle characteristics with extremely wide bandwidths, sometimes spanning multiple octaves. Detecting such broad bandwidths with high sensitivity is itself a challenge, as incoherent measurement techniques often suffer from high noise levels, and interferometric methods such as Fourier transform interferometry often lack sensitivity in the THz range.

Fortunately, another remarkable advantage of the THz pulses generated with ultrafast laser-driven techniques is their phase stability. In other words, all the pulses in the THz pulse train have the same electric field structure in amplitude and phase. This stability arises because all generation mechanisms closely follow the pulse envelope of the driving laser, providing intrinsic robustness. This represents one of the primary advantages of these sources, as it enables reconstruction of the THz electric field in the time domain by gating the THz signal with short, time-delayed pulses from the driving laser.

[Enlarge image]Most common methods for generating single-cycle THz pulses organized by typical pulse energy required to drive the conversion process. [M. Saraceno]

[Enlarge image]Most common methods for generating single-cycle THz pulses organized by typical pulse energy required to drive the conversion process. [M. Saraceno]

The predominant approach to capturing the short THz electric-field transients in this way involves mechanically scanning multiple time-delayed pulses from the driving laser to fully reconstruct the waveform of each THz pulse with high fidelity. This combination of emitter and coherent detection in the time domain forms the foundation of THz time-domain spectroscopy (TDS).

These time-domain pulse-reconstruction techniques have multiple advantages compared with other methods capable of detecting the wide spectra at hand. First, they capture the temporal electric field structure of the pulses both in amplitude and phase. Transmitting such a beam through a sample therefore provides access to its full dielectric function (i.e. refractive index and absorption coefficient) over a very broad bandwidth. These time-domain techniques also circumvent the need for highly sensitive power detectors in the THz region by instead measuring changes induced by the THz field at the wavelength of the driving laser, where detectors are well established and easily accessible.

[Enlarge image]Schematic of terahertz time-domain spectroscopy using, as an example, optical rectification to generate THz transients and electro-optic sampling to detect the pulses in the time domain. [M. Saraceno]

[Enlarge image]Schematic of terahertz time-domain spectroscopy using, as an example, optical rectification to generate THz transients and electro-optic sampling to detect the pulses in the time domain. [M. Saraceno]

The main limitation in this area is the necessary trade-off in measurement speed originating from the need to scan a delay line to reconstruct a single pulse. This limits the refresh rate of a single pulse to the speed of the delay rather than the repetition rate of the driving laser.

Higher average power opens the door to faster acquisition of these broadband THz transients. THz average power represents the direct product of pulse energy and repetition rate, fundamentally determining the signal strength achievable within short measurement durations at given data-acquisition rates.

A higher average power of the THz pulse train results in stronger single pulses or in an increase of the number of pulses per unit time—both of which can improve detection capabilities.

A higher average power of the THz pulse train results in stronger single pulses or in an increase of the number of pulses per unit time—both of which can improve detection capabilities in different ways. Many experiments require a minimum peak electric field or pulse energy to be available; in such cases, a higher average power allows access to this same pulse strength at a higher repetition rate. Such increased repetition rates, in turn, provide multiple advantages that directly impact experimental capabilities. The Nyquist criterion fundamentally restricts the signal bandwidth to values below half the laser repetition rate. Elevated repetition rates enable a broader signal bandwidth within the laboratory timeframe, allowing for more efficient conversion from light time to laboratory time during the detection period.

Furthermore, high-repetition-rate operation provides additional noise reduction beyond simple averaging, as elevated repetition rates distribute signal content across a broader range of laboratory frequencies. Since electronic noise typically increases at lower frequencies (called 1/f noise) at lower laboratory frequencies, expanding the relevant signal bandwidth to higher frequencies results in an improved signal-to-noise ratio.

Finally, acquiring numerous traces per second with high-repetition-rate systems also enables advanced statistical methods and correction algorithms for post-processing of the acquired data. Large trace ensembles support sophisticated data-processing techniques that enhance measurement quality and extract additional information from the acquired data.

High-power lasers to the rescue

The low average power of most THz-TDS systems is due to two factors: 1) the low conversion efficiency from the near-infrared to the THz spectral domain, and 2) the limited output power of most commonly used driving ultrafast lasers. The large difference in driving photon energy (e.g. 1 µm for Ytterbium (Yb) laser) and generated THz photon energies (1 THz corresponding to a wavelength of 300 µm) intrinsically limits conversion efficiency in most schemes to a fraction of a percent, with record values in the few-percent range. This exacerbates the need for very-high-power ultrafast drivers to generate high power THz light—even when considering highly optimized setups.

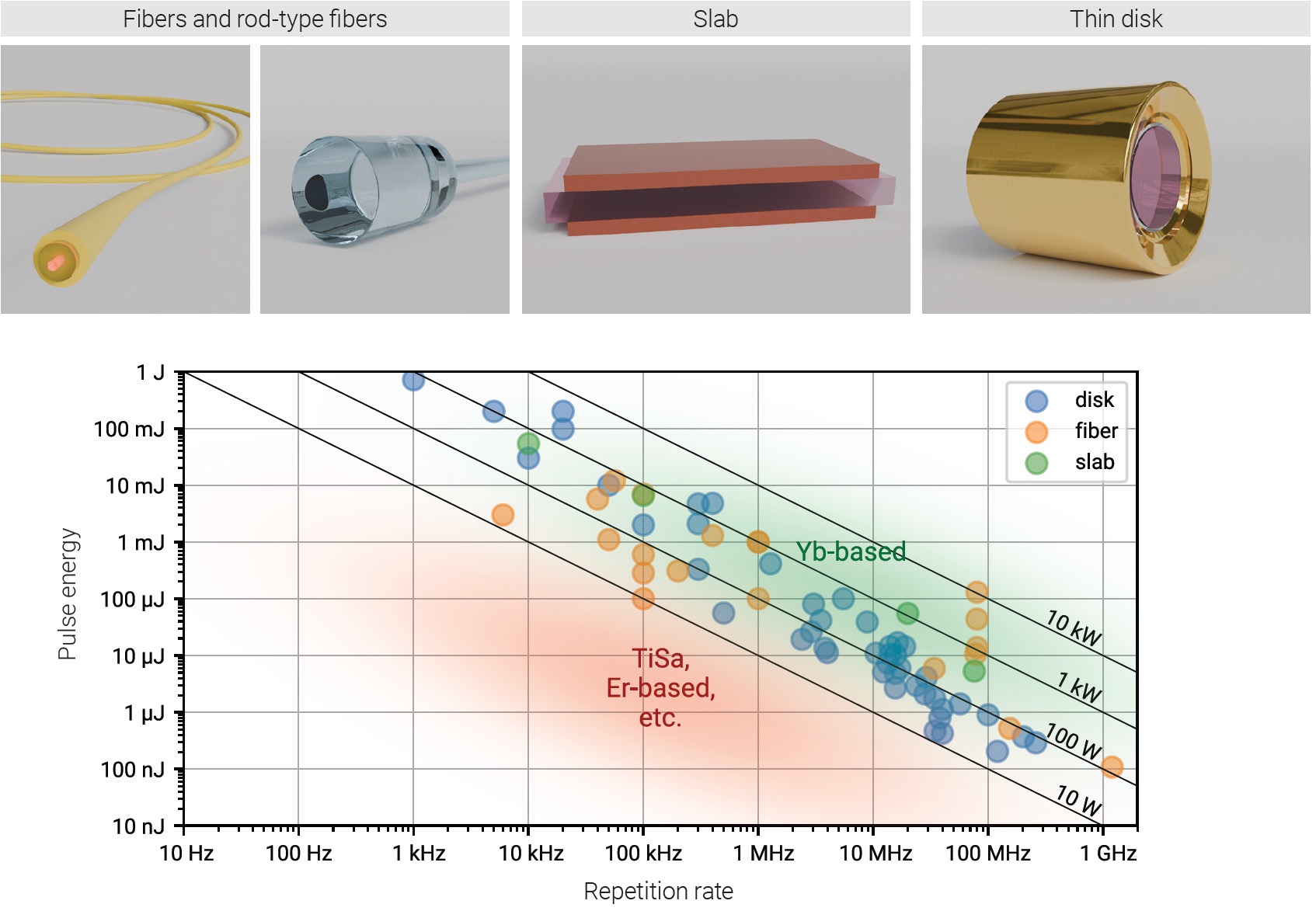

Over the past two decades, there has been spectacular progress in high-average-power ultrafast laser technology based on Yb lasers, providing hundreds of watts to kilowatts of average power across a wide range of repetition rates and pulse energies. Yb ions offer major advantages for high-power laser operation in different laser host materials, including a very small quantum defect—less than 10% of the difference between the pump and laser wavelengths, representing the strongest heat source in a laser—as well as long lifetimes and large emission and absorption cross-sections. These properties make Yb an ideal material that can be efficiently pumped with low-brightness, high-power diodes. When combined with advanced cooling geometries for the laser medium, such as heat-sinked disks, slabs and fibers, the Yb platform provides an excellent foundation for power scaling.

[Enlarge image]Main laser technologies for high-power ultrafast lasers based on Ytterbium and state-of-the-art laser systems in terms of pulse energy and repetition rate. [M. Saraceno]

[Enlarge image]Main laser technologies for high-power ultrafast lasers based on Ytterbium and state-of-the-art laser systems in terms of pulse energy and repetition rate. [M. Saraceno]

Additional nonlinearity-management measures made it possible to bring high-power performance to ultrafast operation. Chirped-pulse amplification methods are commonly applied to reach very high pulse energies, approaching the joule level, while maintaining high average power. Nowadays, robust, turn-key Yb systems are commercially available, offering high stability compatible with both scientific and industrial applications. Additional progress in pulse-compression techniques has further reduced the pulse durations of these lasers—typically in the order of several hundreds of femtoseconds—into the realms of Titanium (Ti):sapphire systems, accelerating their widespread adoption in the THz community.

Breakthroughs in Yb-based ultrafast laser technology have accelerated the development of broadband THz sources with very high average power, enabling several record-setting systems.

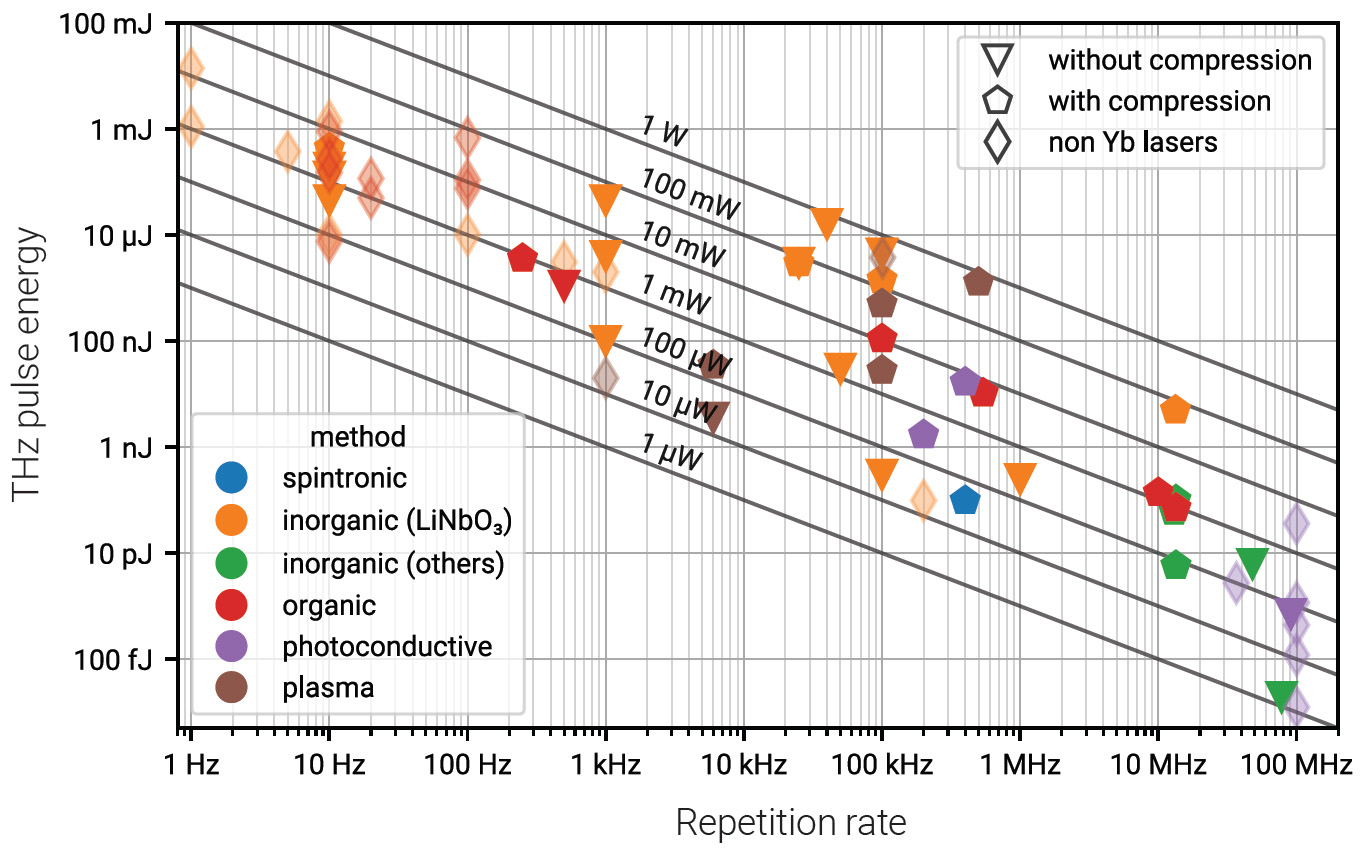

These breakthroughs in Yb-based ultrafast laser technology have accelerated the development of broadband THz sources with very high average power, enabling several record-setting systems in recent years that are now approaching the watt level. These include some of the highest-average-power THz pulsed sources demonstrated to date. Most recently, 643 mW of THz average power with 1.5 THz spectral bandwidth at a 40 kHz repetition rate was achieved using optical rectification in the nonlinear crystal lithium niobate. This source delivers high THz pulse energy (16 µJ), while still operating at a high repetition rate, enabling fast scanning methods that are very promising for accelerated spectroscopy applications. Using ionized gas plasmas, similar average power levels of 640 mW have been achieved with bandwidths exceeding 10 THz at 500 kHz repetition rates.

The pronounced progress achieved in the past few years was possible thanks to detailed exploration of how THz generation mechanisms respond when average power is increased. In nonlinear crystals and semiconductors, most research is focused on heating and damage due to linear and nonlinear effects. In gases, accumulation effects (such as hydrodynamics and chemical accumulation) are active areas of study for understanding how to scale average power.

[Enlarge image]State of the art of laser-driven THz time-domain spectroscopy systems in terms of pulse energy and repetition rate. [Photonics and Ultrafast Laser Science Group, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany]

[Enlarge image]State of the art of laser-driven THz time-domain spectroscopy systems in terms of pulse energy and repetition rate. [Photonics and Ultrafast Laser Science Group, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany]

These advances are currently happening at the intersection between traditional low-repetition-rate strong-field THz sources—typically used for THz-pump applications in spectroscopy and fundamental science—and high-repetition-rate setups driven by Ti:sapphire oscillators or Erbium-doped fiber lasers, which are mainly applied in linear spectroscopy, including imaging and inspection.

Today, Yb-based ultrafast laser technology is playing a key role in merging these two areas. Setups that require strong individual THz pulse strengths can now operate at high repetition rates and benefit from faster acquisition, while setups that more critically require speed and fast averaging can benefit from higher single pulse strengths. This convergence allows laser technology based on Yb-doped gain crystals to bridge disciplines and know-how that were once disconnected. These advances hold the potential to revolutionize the applications of THz-TDS systems.

The future is bright for high-power THz

Several challenges remain to fully unlock the potential of these new high-power THz sources in applications. Further improvements in average power in the THz region (into the multi-watt regime) using very high-power drivers are expected, benefiting from engineering innovations such as better nonlinear crystal cooling geometries and the development of novel nonlinear materials. These gains will be supported by the continual rise in driving laser average powers across repetition-rate regions.

In parallel, efforts to increase conversion efficiency are also ongoing. Current NIR-to-THz conversion efficiencies remain very low, and the cost of high-power driving lasers could become a bottleneck. This calls for alternative enhancement strategies beyond simply increasing the driving laser power. Several areas are currently being explored, including the use of local field enhancement in the near-field, resonant enhancement in cavities or tailoring the laser driving wavelength to enhance conversion. Longer wavelengths, in particular, seem to offer advantages by reducing deleterious nonlinearities and enabling more efficient generation.

The applications of such high-average-power sources are still in their infancy, and many aspects remain to be explored. As average powers in the THz domain continue to increase, studies on dosimetry in this wavelength region will gain relevance. Likewise, thermal effects induced by powerful THz pulses will need to be considered in application design, calling for advanced sample geometries. Finally, the development of highly sensitive, rapid detection methods—up to the single-shot regime for THz time-trace acquisition—will be critical to fully exploit these new sources.

Tim Vogel, Robin Löscher and Clara Saraceno are with the Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum, Germany.

References and Resources

-

R. Löscher et al. “Laser-driven few-cycle Terahertz sources with high average power,” https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.11501 (2025).

-

A. Leitenstorfer et al. “The 2023 terahertz science and technology roadmap”, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 56, 223001 (2023).

-

M. Koch et al. “Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy,” Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 3, 48 (2023).