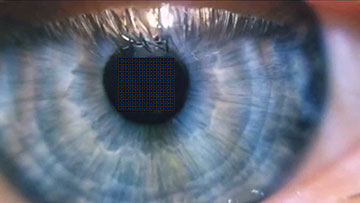

Newly developed submicrometer pixels could be used to create a display small enough to sit just above someone’s eye, with a resolution similar to that of the human retina. [Image: Nature]

Scientists in Sweden have made a new type of miniature pixel comparable in size and resolution to the photoreceptors in the human eye (Nature, doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09642-3). They say that their technology, based on electrically tuneable nanometer-scale patches of tungsten trioxide, could prove ideal for virtual-reality headsets.

Toward smaller displays with higher resolution

The increasing popularity of virtual reality and other immersive technologies is stimulating researchers to develop ever-smaller displays with higher resolutions. But meeting the ultimate requirements of vision at such close quarters is proving a challenge.

In the latest work, Kunli Xiong of Uppsala University and colleagues set out to develop a display technology that approaches the resolving limits of the human retina. They assumed a display aperture of 8 millimeters—the diameter of human pupils in low-light conditions—and a 120° field of view, which they say requires around 23,000 pixels per inch. The researchers point out that this figure would be even higher under normal lighting (when the pupil is smaller) but say the finite distance between pupil and display in any real system would offset the difference.

Most electronic displays today are built with pixels that emit light. But shrinking such pixels below a certain size creates a headache for developers, since reduced dimensions lead to lower brightness, more variation in output from pixel to pixel and unwanted merging of different colors. These problems currently limit commercial smartphone displays to around 450 pixels per inch.

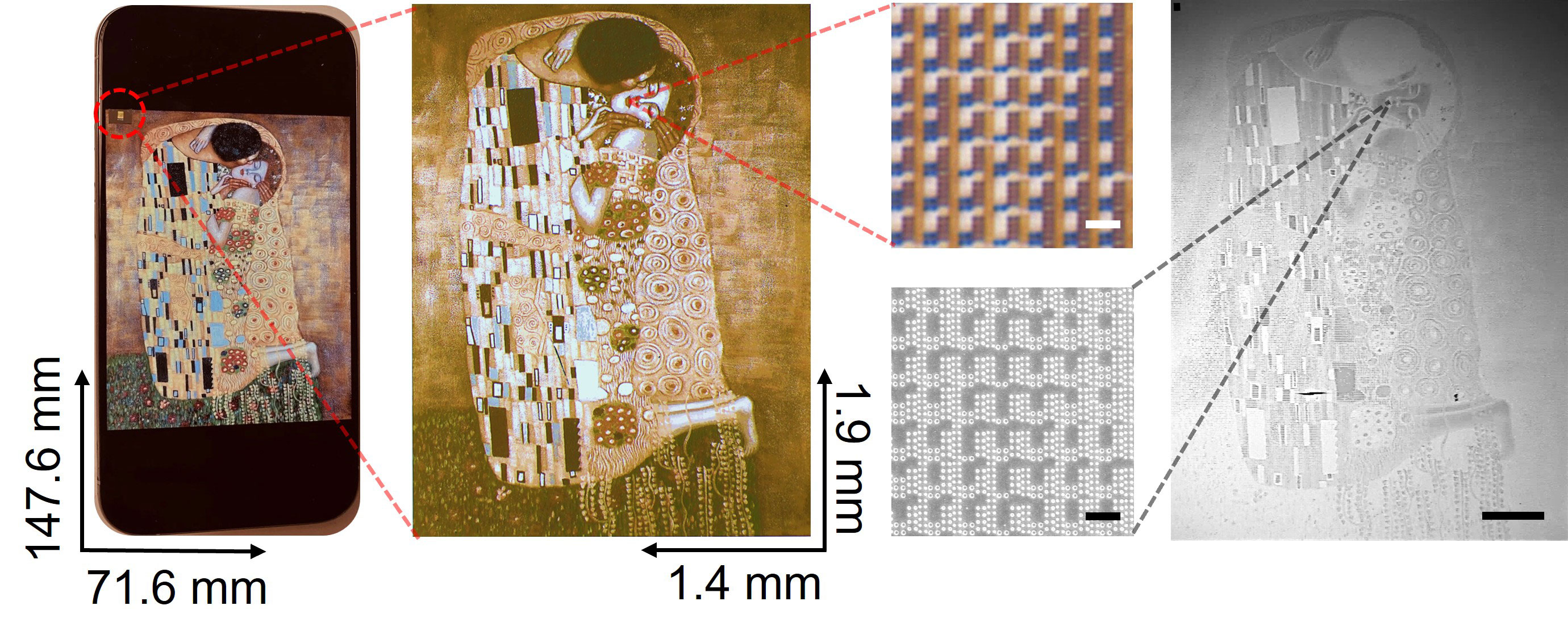

Side-by-side comparison of Gustav Klimt’s “The Kiss” on retina E-paper and a smartphone. The retina E-paper is roughly 1/4000 the size of the smartphone screen. [Image: Nature]

Xiong and coworkers have instead opted to improve on passive displays, which generate colors by reflecting different wavelengths of ambient light. They have developed what they call retina E-paper, made from tiny discs of tungsten trioxide whose precise size and spacing determine the wavelengths of light they reflect. Applying a voltage to the discs switches them from an insulating to conductive state, reducing their refractive index and lowering the intensity of reflected light. By sending specific trains of voltage pulses to different colored pixels, it becomes possible to generate both static and moving images.

Achieving higher resolution

To put their technology to the test, the researchers fabricated nanodiscs using standard semiconductor processes, immersed the discs in an electrolyte and placed them in contact with an electrode. Positioning that electrode just 500 nanometers from another of opposite polarity, they sat the electrodes on top of a reflective layer of aluminum that in turn rested on a platinum substrate. Illuminating the setup with white light, they recorded the intensity of reflected light from the discs.

Xiong and colleagues needed at least four discs to generate each single-colored pixel, but they could maintain both high reflectance and optical contrast even for pixels as small as 400 nm on a side. This, they say, corresponds to a resolution of beyond 25,000 pixels per inch.

The researchers found they could almost completely switch the pixels between light and dark states in under 40 milliseconds—which corresponds to a video display operating at more than 25 frames a second. They also made significant energy savings compared with both emissive displays and other types of E-reader, needing a little more than three times as much power for video as for stills (the pixels’ reflectance gradually decreasing without some external power).

By carefully adjusting the distance between different colored pixels to merge the red, green and blue reflected light into cyan, magenta and yellow light, the researchers also showed they could generate two different colored images that, when combined, recreate a three-dimensional butterfly. They also generated a high-resolution version of Gustav Klimt’s “The Kiss,” showing they could modulate the painting’s colors electrically.

Xiong and colleagues reckon that their technology would be well suited to both virtual-reality headsets and augmented-reality applications, arguing that the displays’ modest power requirements could potentially be met by solar cells, making them entirely self-powered. But they caution that they still need to improve the pixels’ color range, stability, lifetime and refresh rate, ideally pushing the latter up to 60 Hz.

One further challenge, they add, will be developing the very high-resolution arrays of thin film transistors needed to independently control each individual pixel. If they can do that, says Xiong, they then plan to use the new technology to display videos.